More than 100 years ago, possibly on his way home from school, a little boy named Archie possibly popped into a mom & pop shop on Gloucester Road.

He may have grabbed some candy. Probably picked up some funnies too. Maybe Funny Wonder with Charlie Chaplin. Archie adored Charlie Chaplin.

Just maybe.

That news and magazine shop was run by Mrs. Wyatt, who wore her hair piled atop her head. She had inherited the shop from her parents. Archie went to school right around the corner, and was known to roam the neighbourhood’s hilly streets.

The long-ago news shop is now the Room 212 gallery, owned by artist Sarah Thorp. It’s not only her place of business, it’s her home; she lives upstairs from the art gallery.

While she doesn’t know for sure if Archie Leach ever stepped inside her home — she just assumes — she’s always been interested in close-by stories.

And the best story is one that’s passed around.

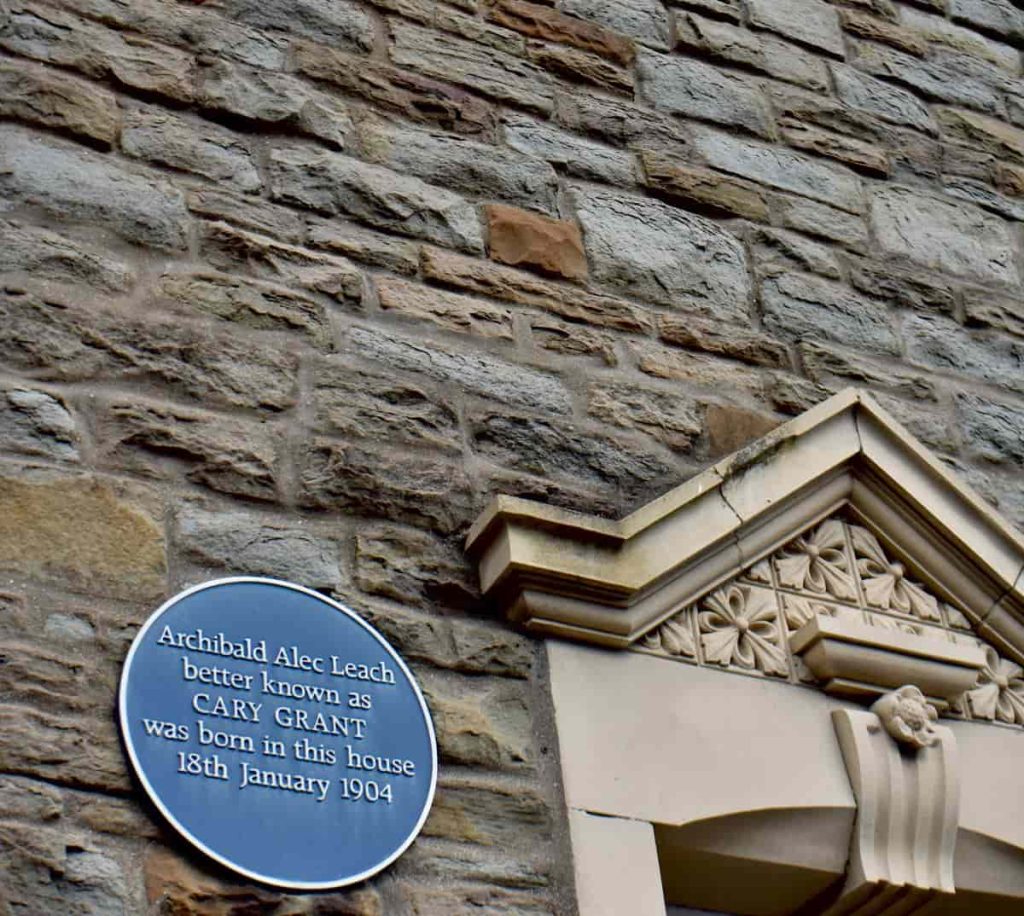

As this story goes, that little boy — Archibald Leach — grew up to be someone big. Maybe it’s the little boy or maybe it’s the movie star Archie became, whose presence still dwells on Bristol streets. It’s here where he was born in 1904.

But it’s Archie’s second incarnation — mega movie star Cary Grant — whose street portrait peeks at passersby from the outside wall of Sarah Thorp’s shop.

In fact, a friend who lives in the flat directly across the road says that the picture of Grant waving hello from the side of the gallery peeks right into her living room.

“And as you come up the stairs … and you look out through that window opposite you, he is waiting,” Thorp said.

He is indeed.

In Bristol like nowhere else, the two sides of Cary Grant — the West Country boy and the dashing movie star — walk together in each other’s story.

“I began by acting like the person I wanted to be, and eventually I became that person,” Grant once confided.

Cary Grant? In Bristol?

More than 20 years ago, reporter Xan Brooks wrote in The Guardian about Grant’s none-too-obvious connection with Bristol.

“Today, (Cary) Grant registers as a flitting, ghostly presence” in his hometown, Brooks said. In fact, many Bristonians, at the time, had “only a foggy notion of who he was and what films he appeared in,” he said.

That was about to change.

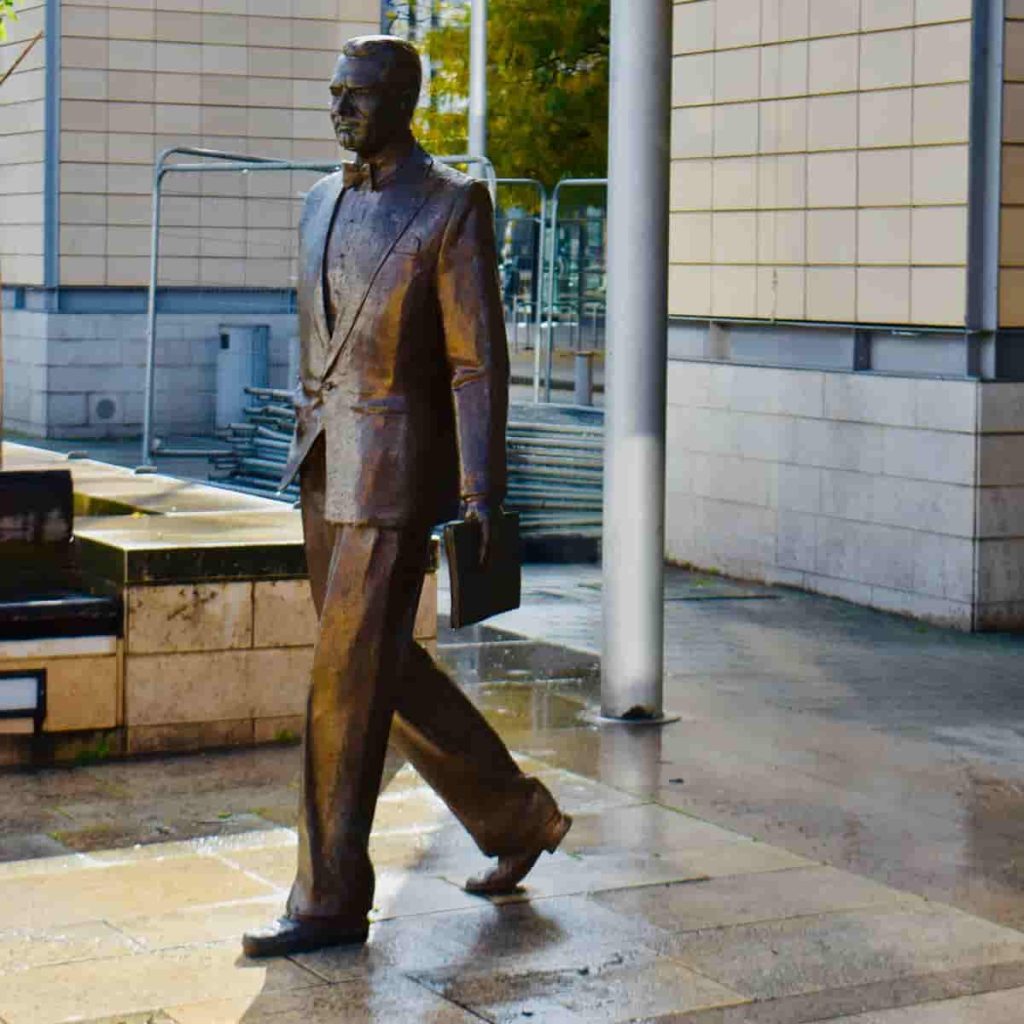

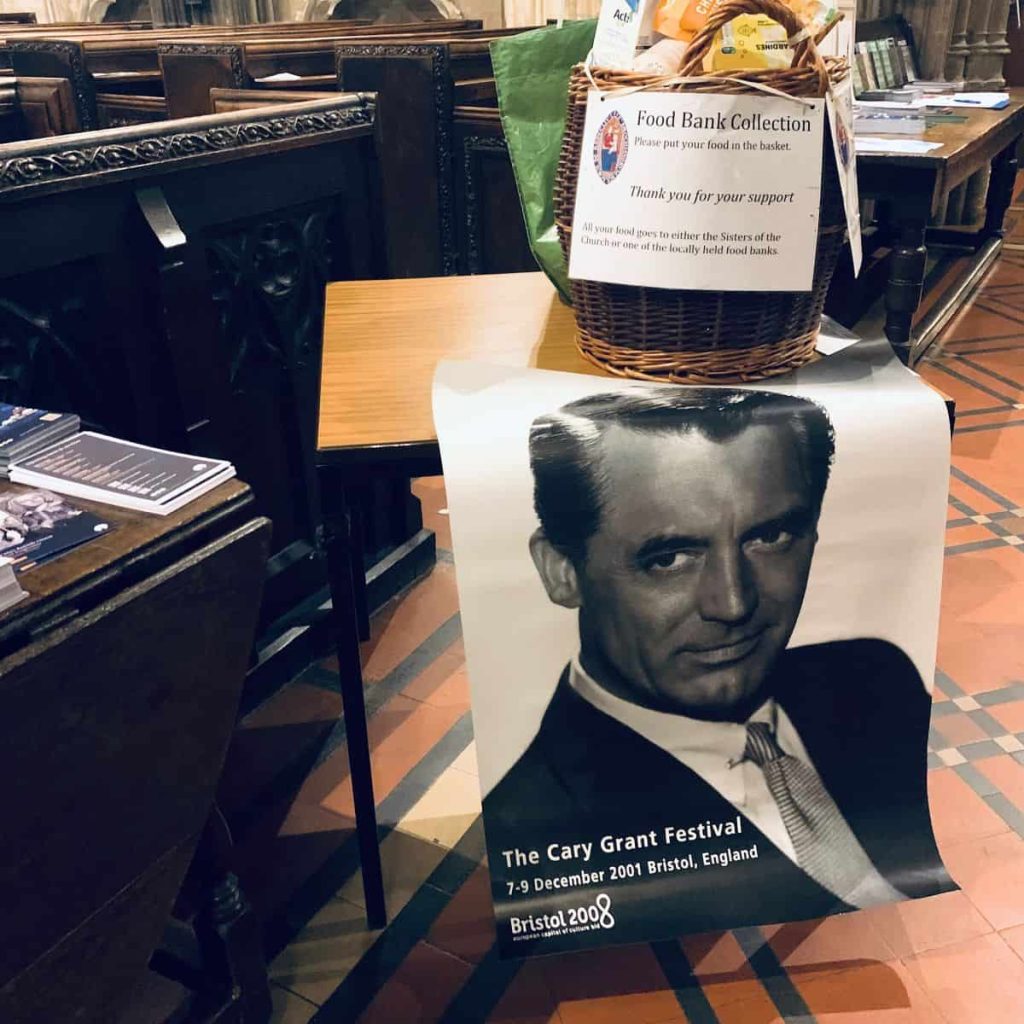

First, in 2001, there was a public campaign to erect a life-sized bronze statue of Grant, which today graces the city’s Millennium Square, Brooks noted. And a “mammoth Cary Grant retrospective” of film was also about to take place in London. Later, came books, documentaries, and today, a brand new television series titled, Archie, on ITV last autumn.

But more than anything, it was a new biennial festival — titled Cary Comes Home — which took that “ghostly presence” and made it relevant. The festival was to become a permanent presence in Bristol, bringing movie star fans from all over to bask in the glow of their favourite silver screen idol.

Festival visitors enjoy Archie/Cary walks, themed talks, and movie showings in iconic Bristol settings. This has included the Bristol Cathedral, St. Mary Redcliffe Church and the Bristol Hippodrome, where Archie worked as a young boy.

It all began with now festival director Charlotte Crofts, whose passion for film, cinema and Bristol found its perfect partner in the most starry Bristonian of them all. That, of course, is Bristol’s very own Cary Grant.

“I am Bristonian, but I didn’t know anything about Cary Grant when growing up in Bristol,” Crofts said. “It was only when I returned and I was studying Bristol cinema history. So I’m really interested in cinema-going and the built environment of cinema.”

Crofts is an associate professor of filmmaking at University of the West of England. Her research is curation, programming and screen heritage. She’s also involved in Bristol’s UNESCO City of Film, a celebration of the “vibrant base” of filmmaking and TV in the city.

(Cary Grant’s legacy is a sparkly, but only a small part of Bristol’s cinematic tradition. The city’s legacy includes the BBC Bristol studios, a leader in nature filmmaking since 1934.)

Crofts’ interest in Grant began when she created various apps of the physical history of cinema in the city.

Clare Street and other Bristol Cinemas:

Crofts said she also learned about Grant’s connection to the Bristol Hippodrome, still a centre of live entertainment today.

In a stroke of stardust, a teacher who worked in Archie’s school did lighting at the Hippodrome in his off-hours. He invited Archie along after school one day.

Young Archie — who would take a job as gofer at the theatre — was immediately smitten.

“And that’s when I knew!” biographer Mark Glancy quoted Grant saying years later.

“What other life could there be but that of an actor? They happily travelled and toured. They were classless, cheerful, and carefree. They gaily laughed, lived, and loved.”

Crofts marvelled at the Hippodrome connection.

“I learned that when the theatre converted to a cinema in the 1930s, they showed six Cary Grant films. And I just thought, Oh my God! So he worked there as a boy, and then in the 30s, they show his Cary Grant films there. I just loved the circularity of it. Wouldn’t it be amazing to put a film on in the Hippodrome? That’s where the idea for the festival came from.”

In launching the biennial festival, which began in 2014, Crofts started small. (Anna Farthing, now festival consultant, was co-founder.) Entertainment at the first festival featured a Cary Grant double bill at the Hippodrome.

“I’m really interested in how Cary Grant’s engagement with culture through the Hippodrome transformed his life and how the arts and creativity can transform people’s lives now,” Crofts said.

The festival continued in 2016 and 2018, going online during the pandemic year of 2020. Off-year activities have included additional movie showings and last November, a new walking tour by the Show of Strength Theatre Company. More tours by the company are now underway.

Every festival builds on Grant’s connection to his hometown, but increasingly, the question is what exactly Grant can do for Bristol today?

To that point, the 2022 festival theme was class.

“It’s really looking at how Cary Grant’s upbringing in Bristol,” Crofts said, “Can it be a point of departure for thinking about social mobility and identity and self-awareness, creativity and how, with his engagement in the arts, it was a part of his becoming Cary Grant?”

In showing two “Cockney Cary” films – None but the Lonely Heart and Sylvia Scarlett – the festival looked at “the contract between Archie and Cary, the two different sides of him.” In these films, Grant played working-class characters, a nod to his own Bristol boyhood.

Taking a different twist, in 2024, the festival’s theme will be circus and theatre, Crofts said. It will highlight a Bristol circus troupe and young circus scholars, giving local performers the chance to tap into Grant’s legacy. Likewise, the festival will also recognise Grant’s own acrobatic skills and movement in films.

Archie Leach, The Acrobat

Those physical skills, which so defined Grant’s comedy, were first nurtured when Archie, at 14, ran away from home to join Bob Pender’s traveling acrobatic and comic troupe, fudging his fathers name on an introduction letter.

(This was shortly after he had been expelled from what was then Fairfield Grammar School for sneaking into the girls’ toilets. It’s a favourite Bristol tale, maybe because Grant himself liked to tell it.)

It was in Bob Pender’s troupe where Grant learned to be an acrobat, stilt walker, juggler and mime. “This slapstick apprenticeship shaped the performer he became,” said The Guardian’s Brooks in another news article in 2013.

Unlike so many Hollywood stars, Brooks said, Grant could do both the comedian and the smouldering leading man.

“Along the way, Grant came to embody, simultaneously, a gilded romantic hero and a prat-falling chancer. He was Cary Grant and he was Archie Leach, with each man aware of the other’s existence and each delighting in the dance,” Brooks said.

Famous Cary Grant Pratfalls:

It’s that Archie/Cary duality that festival goers and other Bristol pilgrims explore today.

Rachel Austin-Francis attended her first Cary Comes Home Festival in 2022, both online and in person. She works in mental health and lives in Weston-super-Mare, about 40 minutes outside Bristol.

Austin-Francis, who earned her second university degree in Bristol, said the festival “extended her knowledge” about Grant, although she wishes the community overall better promoted its movie-star connection.

“I think that’s a bit of a shame,” she said. “I think they should make more of it. It’s fantastic the way this festival does. But when you think that such a major star (lived here), it really it ought to be publicised” more by the city.

Through the festival, she learned about some of the Bristol places linked to Archie Leach, like his birthplace. “It’s incredible to think I was going around the same places he had,” she said. He was “always one of my favourite actors.”

She likes the idea of the festival bringing like-minded movie fans together.

“It’s sort of nice to be able to share that with people because I find very often that people aren’t as interested in old films as I am, and when you find someone who is, it’s sort of like in a desert. You leap on them like an oasis.”

A Hard-Luck Kid Falls for the Movies

Austin-Francis, and other fans who travel to Bristol, are often somewhat familiar with young Archie’s harrowing tale and its rags-to-riches ending.

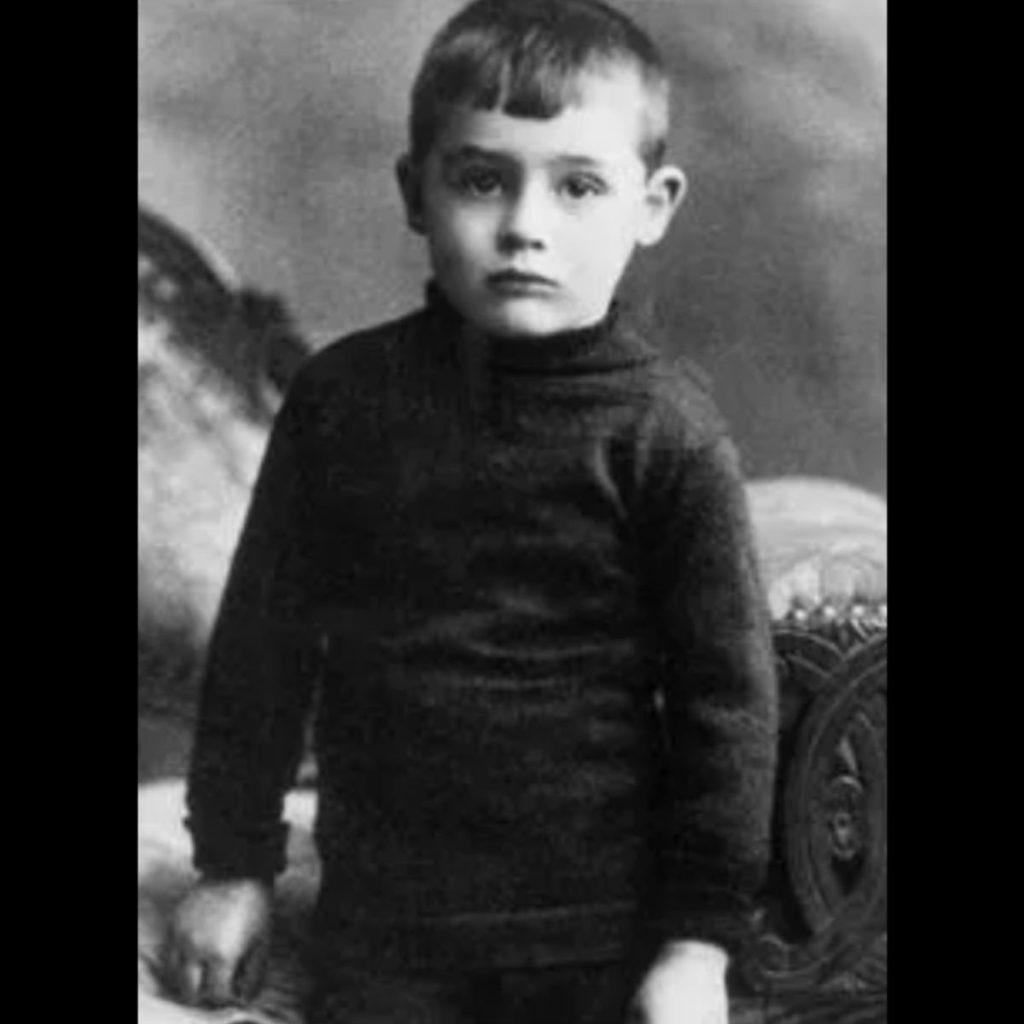

Archibald “Archie” Leach was born in 1904 in the working-class neighbourhood of Horfield, Bristol. A rough beginning, he remembered later, of freezing nights and outside loos, according to his biographer Mark Glancy.

Glancy, author of Cary Grant: The Making of a Hollywood Legend, wrote that the 20 homes on Hughenden Road were built on old farmland at the turn of the last century. They were “tightly packed terrace houses” with a park at the end for running loose.

(To see the houses today, climb off the main street of bustling Gloucester Road and find your way to the one with the blue plaque. Today, you’ll find pretty painted doors, colourful border gardens, and modern skylights — no more the hard-luck homes of Archie’s day. One realtor on Gloucester Road recently estimated that they were worth about £400,000 each.)

Archie’s parents, Elsie and Elias Leach, argued, mostly over money, Glancy said. It was “miserable” marriage, he quoted Grant as saying years later.

Early on, it was the promise of Bristol cinema that sustained a poor kid with little money and unhappy parents. Elsie took Archie to the posh cinema where they served tea and fancy pastry. Elias chose the less fancy movie house, The Metropole, that smelled like “raincoats and galoshes”, Grant remembered years later.

Guess which one the little boy preferred?

Life for young Archie would get darker. Soon after he turned 11, he came home from school to find his mother gone. Visiting the seaside, his dad told him. But she never came back. The story seemed to be that she was dead, according to Glancy’s research.

Except she wasn’t, Glancy said. Only when movie star Cary Grant returned to Bristol nearly 20 years later did his dying father tell him that Elsie was alive. Elias had stashed her in the Bristol Lunatic Asylum, something apparently not that hard to do in the early 20th century. Elias also had a new family.

All this left Grant with a basket-load of trauma to unpack. It’s a horrid, messy tale for biographers to sift through.

Grant’s visits to his hometown would now include some uncomfortable visits with his mother, whom he supported financially. He prompted her release from the asylum eight months after the death of Elias in 1936.

In the years that followed, the Bristol Grant knew as a boy was changed irrecoverably by enemy bombers during World War II. German fighter planes followed the reflection of moonlight on the River Avon straight into Bristol centre. Five family members of Grant’s were killed, including a favourite “Aunt Ro”, Glancy reported.

In a tour of the city with a reporter in 1946, his first visit after the war, Grant was stunned by the devastation, Glancy noted in his book.

“It is a depressing sight to see so much of historic Bristol so badly battered,” he said.

Bristol’s Big-Time, Super Cool Vibe

Yet, while well-known to historians, locals and fans, Grant’s connection to Bristol is not always obvious to every visitor.

For one thing, there’s plenty of competition.

Bristol’s list of famous or infamous inhabitants reads like a who’s who of coolness: The bad and the beautiful. The smart. Explorers, pirates, scientists, and artists.

Darth Vader (AKA actor David Prowse) came from Bristol, for goodness sake, and Blackbeard. An actual premier league pirate.

Never mind the icons of science (such as Isambard Kingdom Brunel, engineer of the Great Western Railway) or exploration (such as John Cabot, founder of a chunk of the New World). To only name a few. Take a walking tour of Bristol’s famous street art to see more cool kids.

That being said, there’s no greater cool kid for fans of mid-twentieth-century cinema than the forever dashing Cary Grant. Enough to even get him his own piece of street art.

Even if he isn’t a pirate.

It started when Sarah Thorp of the Room 212 gallery ran into the Bristol-based street artist, STEWY, at an art show about six years ago. They got to chatting, and she told him how she believed Archie must have come into the neighbourhood store that today is her gallery.

“She was adamant that she wanted (the art) on the building, but there was no space,” STEWY said.

Eventually, he settled on a spot above the door. Then came the search for images. Grant had to be sitting for the image to fit.

“I could only find one picture that would have worked and it was an old picture of him sitting on the edge of building,” STEWY said.

In this photo, Grant is famously sitting on a Paris hotel balcony with the Arc de Triomphe in the background.

STEWY then converted the photo to a stencil and “got a very long ladder”. As it happens, Grant is now just the right height to peer into the windows of buses passing along Gloucester Road.

On his web site, STEWY describes his art as “psychogeographic life-size stencils of animals & outsiders, rebels, misfits and obscure icons representing the best of culture.”

Over the years, stencils have included: Thomas Paine, 18th-century revolutionist and philosopher; Jarvis Cocker, rock musician; Ken Loach, director and screenwriter; Tracey Emin, artist; Vivienne Westwood, fashion designer; and John Cooper Clarke, poet.

“A common theme is they’re all life-sized, like they’re ghosts or manifestations of people,” he explained in an interview. “I’m not trying to make them look totally real.”

And the “theme is always Britishness, who we are,” he said. They appear in alleyways, doors, garden walls, and urban settings, often competing with graffiti, crumbling brick and even scaffolding.

His chosen figures led “lives doing good”, STEWY said, even if that sometimes meant being rebellious or disruptive. Some may have died in poverty, but tried to make the world a better place; some may not be well-known. Those who worked for justice is a favourite theme.

And because a stencil becomes public art, STEWY said, “There’s like an ownership. It belongs to everyone.”

STEWY began making stencils in 2007-8, starting in London and landing in Bristol about 10 years ago.

One day, he took the train to Manchester to find someplace where one of his stencilled figures had a connection. That started the journey of placing people in relevant locations, people important to me, STEWY said.

For example, in a 2013 commission for the Mud Dock Cycleworks in Bristol’s floating harbour area, there are these city icons: Blackbeard on a bike, Darth Vadar on a bike, and Brunel, also on a bike.

So where does Grant fit in this Bristol-based royalty?

Cary Grant is so unique, STEWY said. Like his idol, Charlie Chaplin, “He would have made that journey” to leave home. “You can carry them in your hand the number of British actors who went to America (in the early days of cinema) and made it. It must have taken a lot of guts.”

So Grant, while not a rebel in a typical sense, fits that outsider role of many of STEWY’s figures — an icon coming back, where he started. And he did well.

With Grant, it was a question of “Was he running away from (Bristol)? Was his trying to find a better life? And I don’t blame him for that … But it would have taken a lot of courage at a very young age. Whatever the reasons for leaving,” STEWY said.

Cary Grant Carries Around Bristol

Like other STEWY icons, Cary Grant never fully left where he started.

And likewise, a part of Bristol never left Cary Grant.

As Charlotte Crofts noted, in the Cary Comes Home festivals, “We try to use Cary Grant to say ‘not just isn’t it nice that he came from Bristol’, but to actually understand where he came from, what that means for people growing up in Bristol today.”

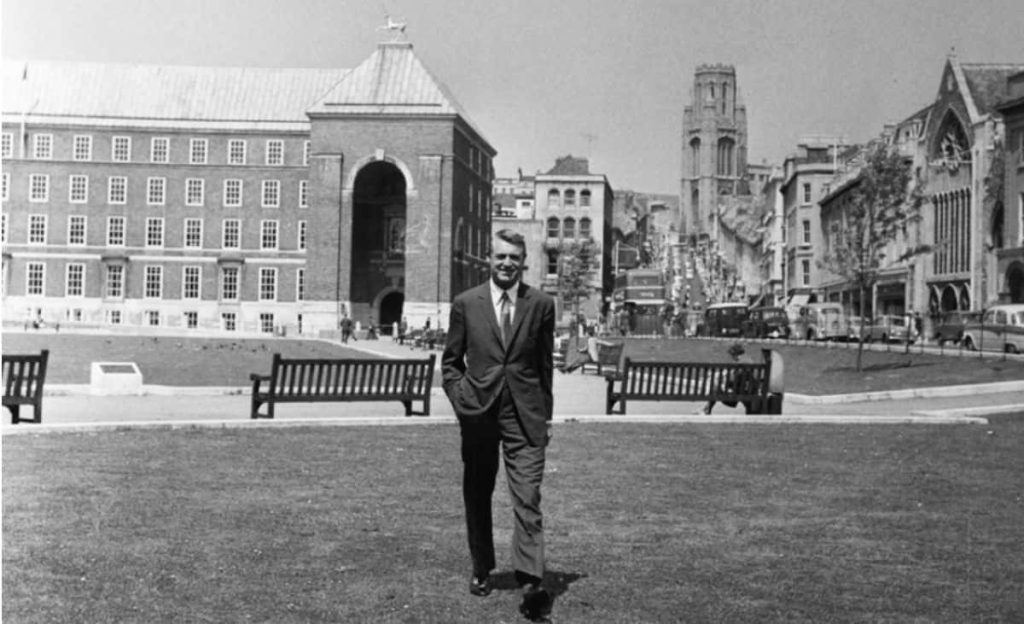

Biographer Mark Glancy wrote that during visits to Bristol over the years, Grant “roamed about” on foot just as he had as a childhood truant.

“I have loved walking about the old streets,” Grant said, “Tripping over the same cobblestones.”

Why did he come back to visit? To see his long-lost mother, of course. Was that the only reason? Or was it to be photographed looking every bit the dashing Cary Grant figure striding across his home city? To visit old haunts?

One thing’s for sure, he didn’t just make an appearance.

Sarah Thorp tells about a story about someone she knew though the gallery.

“There was a lady who made things for the shop,” she said, “And she used to work at the Avon Gorge Hotel in Clifton, (a well-to-do Bristol neighbourhood). Cary Grant used to take his mum there and apparently, one breakfast she was working there, and he was sitting there on his own, and he invited her to come sit with him. She actually had breakfast or lunch with him. He sounded like a very nice guy.”

Another time on a visit, Grant popped on top of the Bristol Cathedral with the dean for a photo op to help raise money to repair the roof.

“This, I love,” he once said. “I enjoy talking back and forth to people. You know, otherwise, I wouldn’t get to meet the people.”

So he didn’t just pose. He stopped at the Hippodrome, not for a quick visit, but for chats backstage. He visited his old school, stayed for awhile, looked through old records. He was a good sport.

At the M Shed, a museum all about Bristol on the harbour side, is displayed a photo of “Cary Grant with Doris Comely of St. Paul’s, Bristol, who won the chance to meet him in a competition” in the 1950s.

And as easy-going as ever, they pose together on a couch, holding teacups in their laps, Doris looking at the camera, Grant, crosslegged, turned toward her, beaming.

Today in Bristol, people still grab photos in front of the statue of Cary Grant, who carries the script of director Alfred Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief as he makes his way across Millennium Square.

Jane and Duncan Hallam of West Sussex were in town visiting the Bristol Museum & Art Gallery when they heard about the statue and made their way to the square.

Jane said she was fan of movies and Cary Grant while taking a few photos by the statue — even one for a women asking her questions.

“He’s so typically British, isn’t he?” Jane asked.

Fans also make their way to the 20th Century Flicks Video Shop on the Christmas Steps, where the favourite Grant DVD request is North by Northwest from 1959.

“A tense and compulsively gripping nice-guy’s nightmare. Obligatory viewing,” according to the shop’s five-star review on its web site.

What We Give

So how to build on that legacy? Both that of the poor boy from Bristol and the dashing movie star?

“He did leave and had a sad childhood, but he was very loyal to the city and he came back,” Crofts said. “So I guess some people say, ‘Well he hated Bristol and he went to Hollywood and he didn’t like Bristol’. But it’s more complex than that. And I think he’s a symbol.

“We can’t all be Cary Grant, obviously. He was an incredible individual. He had a lot of luck, but it also took a lot of hard work to become Cary Grant. But it’s inspiring. And also, Bristol really shaped him. The cinema-going that he did with his mother and father. He saw those slapstick movies and we see that in his performances. All his pratfalls and things.”

Maybe Bristol wasn’t just a place to leave, but a place to fuel a lifetime adventure? As STEWY said, that courage to go?

“Also, his love of travel,” added Crofts. “His wanderlust. We’re a Floating Harbour. He saw all the boats. We used to be a working harbour and the water would come right up into the centre, right past St. Mary-on-the-Quay. Big ships. It was a working harbour until probably the 60s.

“Archie liked to watch the boats, fantasise about sailing away on the tides to escape his sad childhood.

“So that’s where it came from and where it is very much wanting Cary Grant to be important and relevant to inspire people today.”

For Rachel Austin-Francis, it’s a connection with her mother, which she is passing on to her daughter, who lives in Bristol.

Something to pass on.

“I remember thinking back when I was very small, (and) what was the first film I saw of (Grant’s)? It was Penny Serenade and I remember watching it with my mother.

(Grant received the first of his of two Oscar nominations for his performance in this bittersweet drama, which co-starred Irene Dunne as his wife.)

“My mother was a huge film fan. It’s lovely because it’s one of those things that you can share with your children. And with your parents. And they’re classic films aren’t they? They never age.”

Austin-Francis recently watched Houseboat — featuring co-star (and old Grant flame) Sophia Loren — with her daughter.

“I do what my mother did with me in that we had that shared love of film … And we would sit and talk about them and you didn’t realise when you were younger that not everyone else did. You didn’t realise what a special thing it was.

“And I’ve done it with my daughter. We just love it. We’ll sit and watch films together, movies. It’s all the old ones. It’s all the classics. It’s a real shared experience. It’s lovely actually. It’s lovely when you find someone who loves them as much as you did.”

It starts with getting together.

Said Crofts: “I think going to the cinema and going to the theatre sounds like a really simple thing. You take it for granted because you do it all the time, but it can be a life-changing experience. It can be an inspiring moment in your normal day-to-day life. It’s so different from watching television. Our shared experience of watching something in a big auditorium.

“So if I can celebrate that and give people the opportunity to do that, that could be something that shifts for them, that makes them be impacted in a different part of their future.

“We try to use Cary Grant to say, not just isn’t it nice that he came from Bristol, but to actually understand where he came from, what that means for people growing up in Bristol today.”

As Grant himself once said, “Destiny is not necessarily what we get out of life, but rather, what we give.’’

Celebrate the 120th anniversary of Cary Grant’s birth in Bristol – November 2024.

AT-A-GLANCE SCHEDULE

BRISTOL MEGASCREEN SCREENINGS

FRIDAY 29 NOVEMBER

18.30pm Opening Night Reception, with live music from the Atomic Paradise Trio (included in the Weekend Pass) – spaces limited so book now!

19.45pm North by Northwest

SATURDAY 30 NOVEMBER

10.00 I’m No Angel

12:00 Panel: Cary in Motion, exploring the influences of Archie’s acrobatic past

14:00 Panel: Animal Magic, discussing evolving practices of working with animals in film

16:00 Monkey Business

19:00 Bringing Up Baby – with live music from Keep It Vocal choirs (including music from the film)

SUNDAY 1 DECEMBER

10:00 Holiday

13:00 The Awful Truth

15:00 My Favorite Wife

CHRISTMAS SPIEGELTENT

19:00 Closing Night Gala: To Catch A Thief – with live circus performance at Bristol Spiegeltent*

All films are U or PG

MEGASCREEN FESTIVAL PASSES

Standard Festival passes – £60

Saturday Day Pass – £30

Sunday Day Pass – £24*