“Where is Bermuda?” said the Lion anxiously. “Is it a wild place, and is the voyage a dangerous one?”

“Bermuda is the land of sunshine,” replied the steward, “a land of bananas, onions and lilies. You will be welcome there, and we will make your trip pleasant. Have no fear and trust in me.”

— Denslow’s Scarecrow and the Tinman on the Water (1905)

On a July evening in 1905, on a sweltering stage in Boston, Massachusetts, a chorus line of dancing Bermuda lilies rose into the footlights to sing a love letter from a heartsick girl to a missing boy.

These ruffled white lilies were remarkably similar to another pretty flower patch come to life, the one of the magical red poppies in the kingdom of Oz.

But no matter.

These chorus-girl Easter lilies not only blew up the stage in an otherwise white-bread show, they linked two explosive forces: the imagination of William Wallace Denslow — the original illustrator of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz — and the place where he found a welcome muse, the tropical island of Bermuda.

“It is a place for dreamers,” he wrote many years later, when this promising Boston night was but a memory.

For a brief time at the turn of the last century, just before the multitudes of tourists showed up, W. W. Denslow — or “Den” to his friends and colleagues — soaked up the tropical palette of this mid-Atlantic archipelago, finding some respite and inspiration.

For an artist who dabbled in the magical and understood the potential of color to tell a good story, it was a fruitful fit.

These were heady times for artists and wannabe explorers. It was a new century and everyone wanted a slice.

For someone like Denslow, with money to spend and in need of a mental-health break, Bermuda proved an agreeable landing spot.

He bought himself a piece of it, built a tower and declared himself king. A fanciful turn for a man who worked in fantasy.

His very own Oz, if you will.

But the pomp obscured a more basic reality: Denslow was very much a working guy during his time in Bermuda, combing the island on land and sea, looking for that spark. His next big thing.

Did he find it? Depends on how you define big.

Denslow’s late-career, island wanderings didn’t produce another classic. His masterpiece had already been made. Nothing he created in Bermuda, or in the last few years of his life for that matter, came anywhere close to the brilliance of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

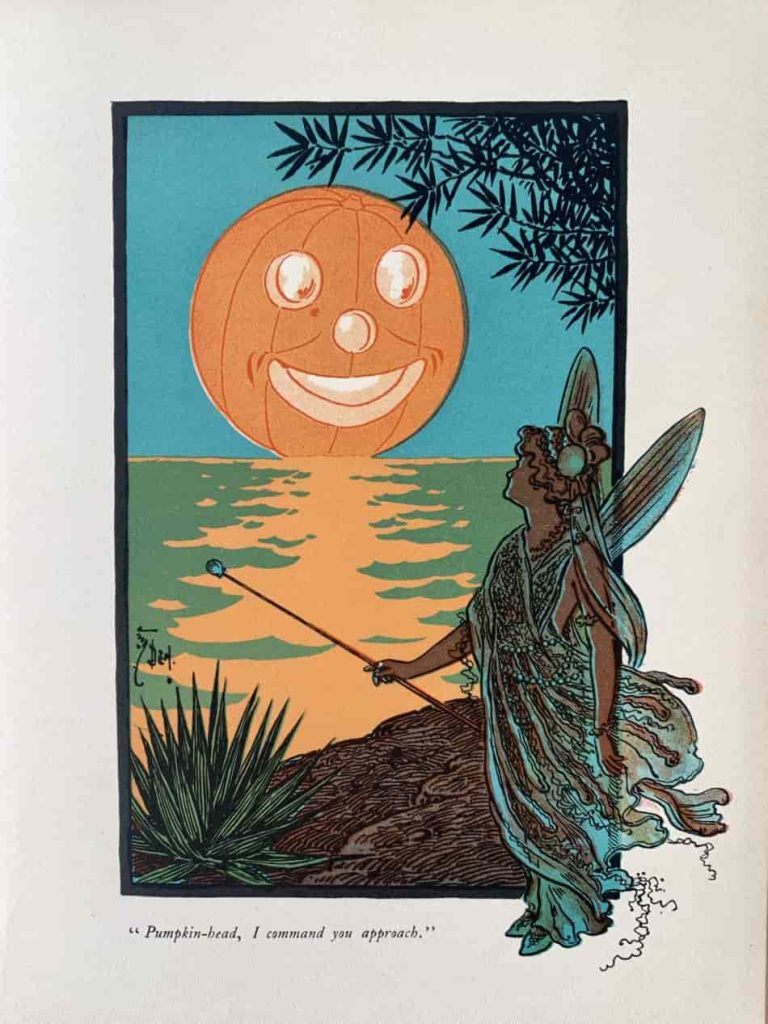

But the artist did find color — that Bermuda pink, blue and more — to fire up his imagination.

He also found a missing spring to his step; a little island swagger, if you will.

And that can go a long way if you know how to work it.

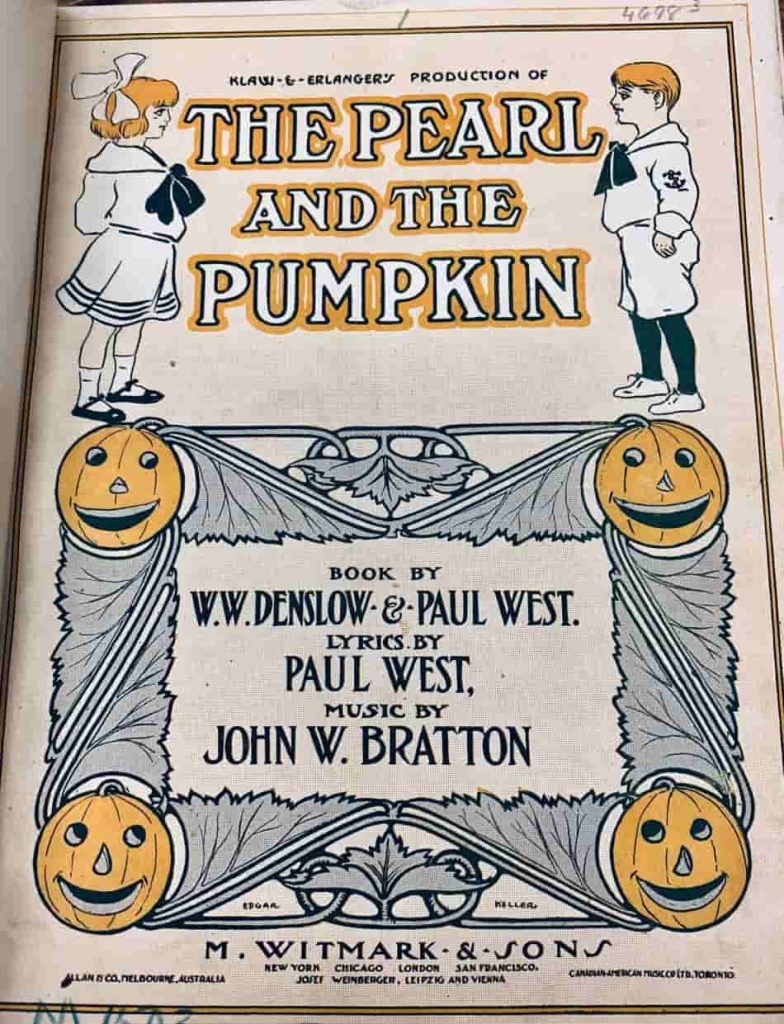

For starters, Denslow took Bermuda to Broadway, a so-called extravaganza called The Pearl and the Pumpkin. Sure the plot was a bit wonky, but it was a spectacle nonetheless, at least for a few short months. It was here that those lilies turned up:

In a field of lilies in Bermuda

Knelt a little maid in tears,

’Twas Easter Morning in Bermuda,

But her heart was torn with fears.

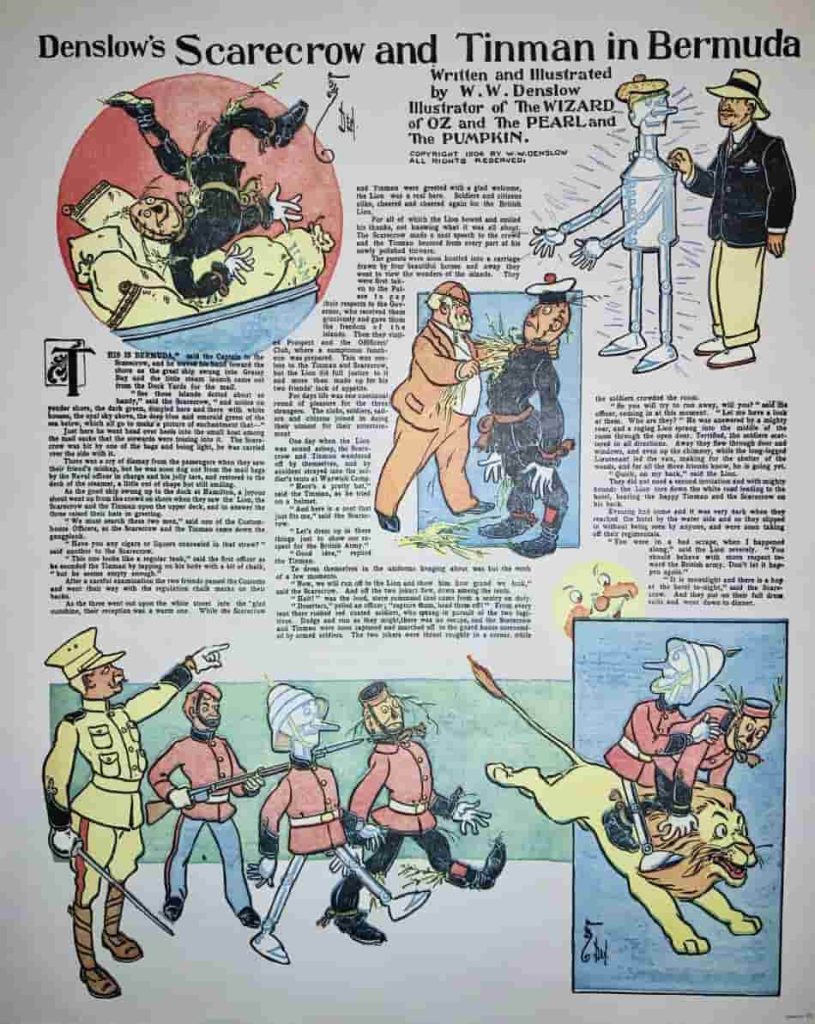

In a short-lived comic strip, the Oz characters came to the island, raising havoc and making merry.

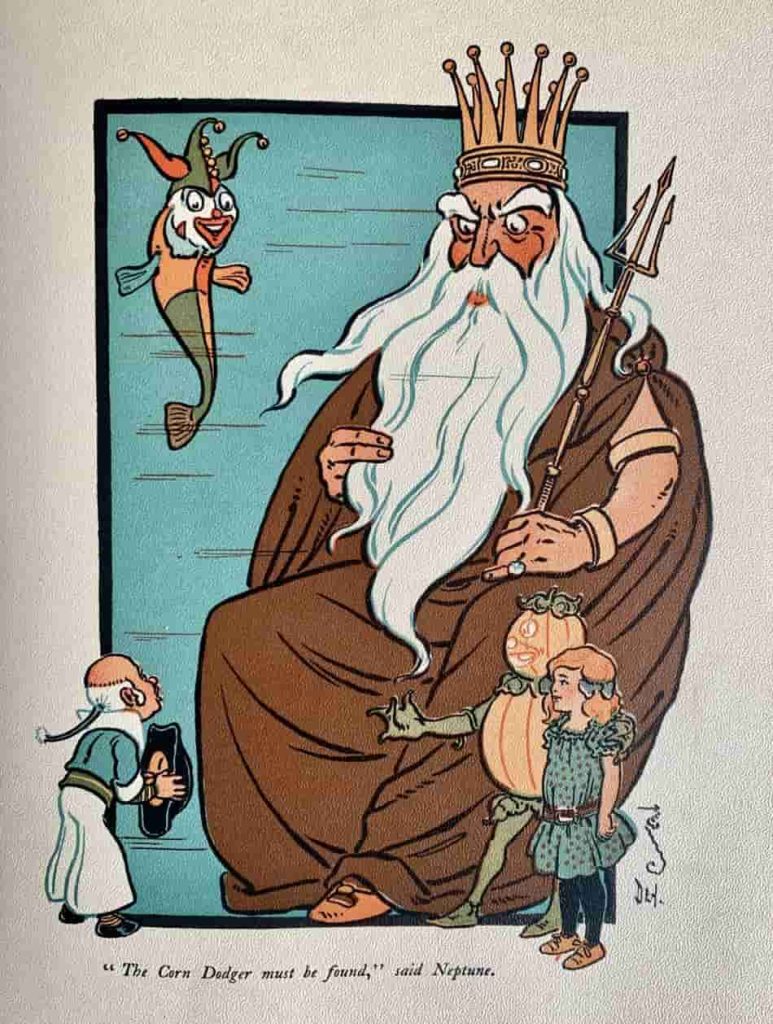

And there also was The Pearl and the Pumpkin book, which preceded the musical, its plot winding its curious way to Bermuda.

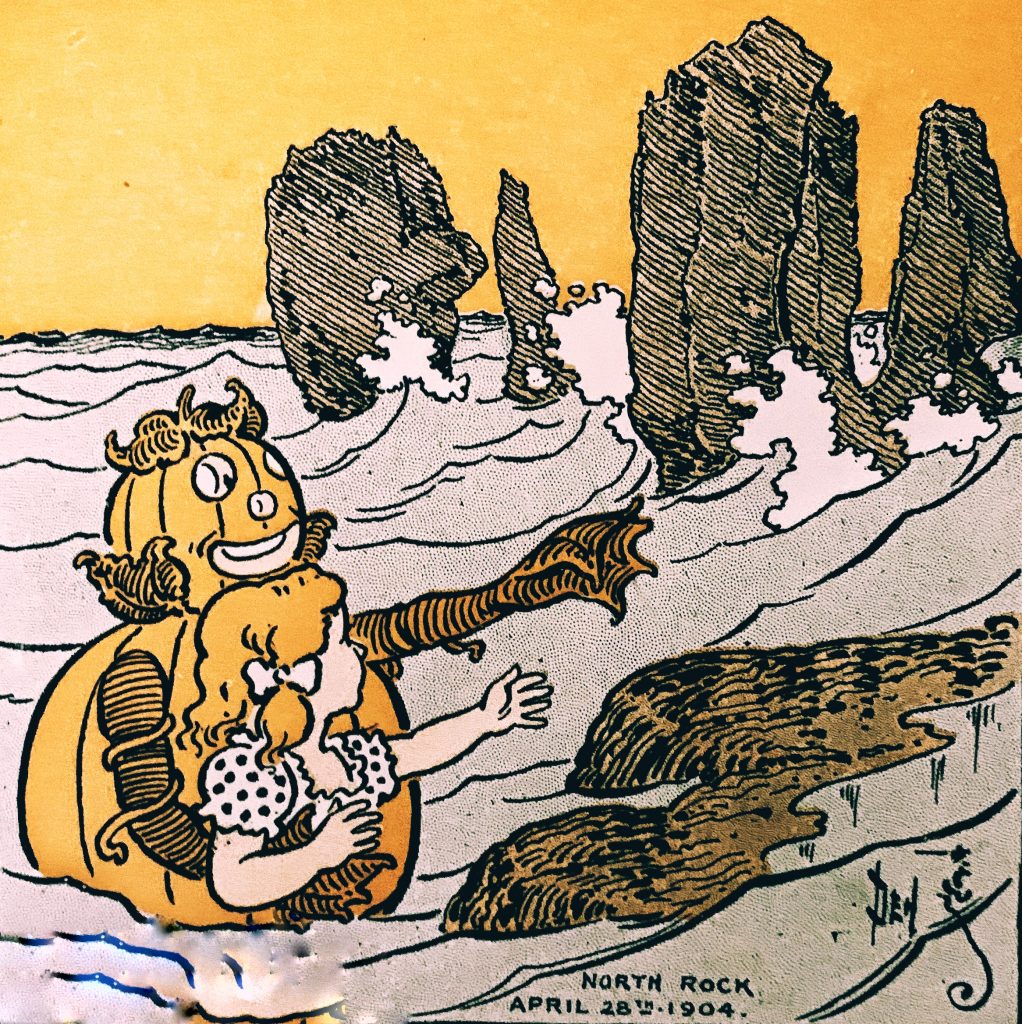

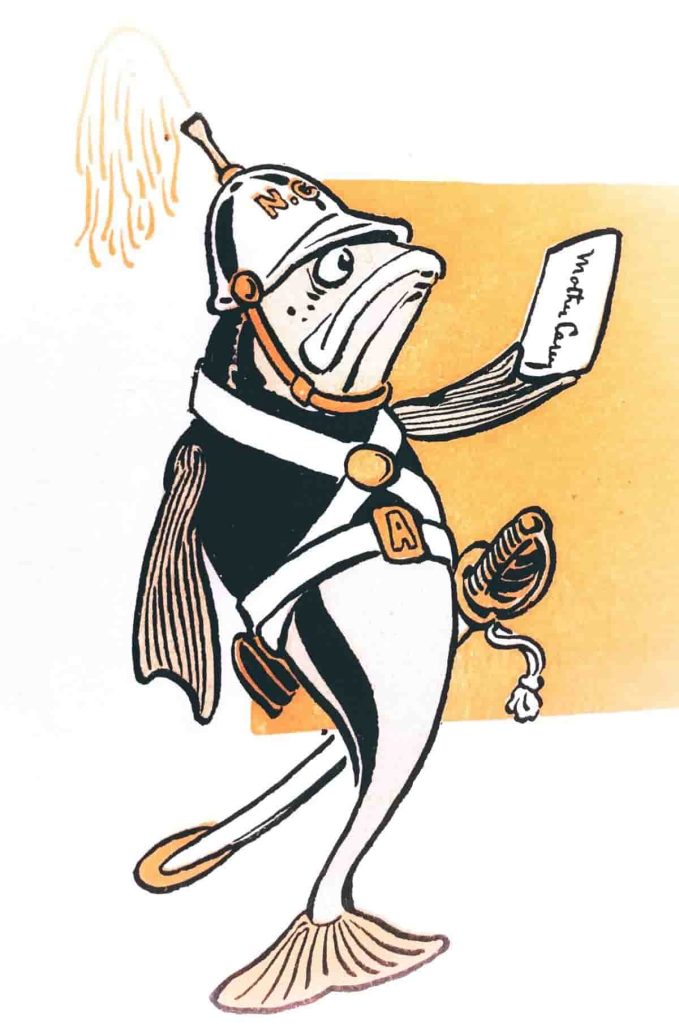

Denslow peppered his work during this time with images of the island. In his book, readers find its famous coral reef, a busy Hamilton Harbour, and the historic Parliament building, alongside Bermuda onions and those Easter lilies. How about a natty sailor, a grouper turned into a palace guard, or a glowing pumpkin rising out of the water like a sparkling sunset?

That’s Bermuda all right, or at least a highly sensational one.

“They’re fun. They’re terrific fun,” said the late Tim Hodgson, a former Bermuda editor and reporter, whose extensive writings on island history included a 2013 piece on Denslow.

“But it’s an imaginary Bermuda,” he said in interview last summer before his sudden death in December at age 57. “North Rock (coral reef) full of mermaids, you know. It’s just where his imagination led him. But you know it’s great. You can say his imagination did lead him there. That he used Bermuda as a source of inspiration. He even worked his own house into one of them.”

Bermuda not only inspired him, it boosted his brand.

“He says what he thinks about Bermuda, or he says what he wants people to believe he thinks about Bermuda,” Hodgson said.

Denslow’s Bermuda Swagger

Setting up shop in Bermuda can certainly be something to brag about, be it an overworked artist in 1903 or an expat in finance today. Basking in the year-round sunshine while your East Coast colleagues shiver through winter.

It’s also not a bad place to spend your profits. Another thing that hasn’t changed in more than a century.

Initially, Denslow’s Bermuda stay was simply an attempt to revive his health, his creative spark, and his failing marriage. Money from a new Oz show, based on the best-selling book, lined his pocket.

It later turned it into something bigger, a place to tell his own colorful tale.

“Although it is midwinter, my little daughter and myself at 7 a.m. go off the dock in the clearest and saltiest water in the world,” he said in a newspaper piece several years later.

“This is a specimen of what the Summer Islands are, a land of beauty and joy forever.”

It all began with a brave little girl, some supportive friends, and a trip down the Yellow Brick Road.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

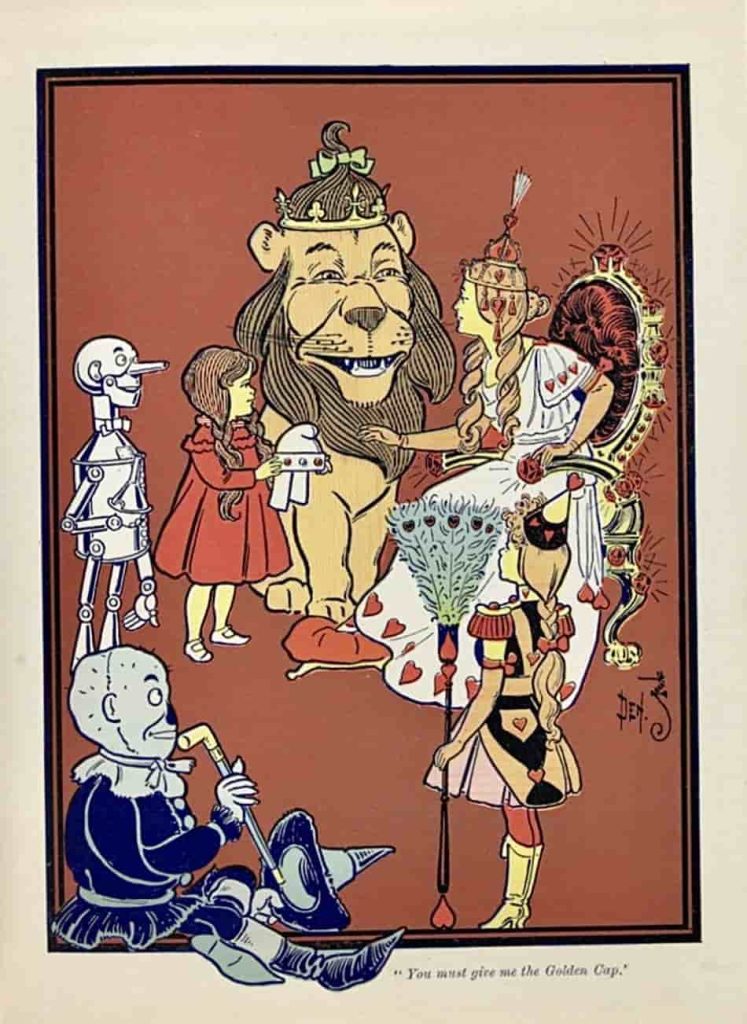

In 1900, three years before those Bermuda dreams, Denslow had teamed up with author L. Frank Baum to create The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, a uniquely American fairy tale that shook the publishing world and dazzled young readers.

It was a new book for a new century, dripping with color and graphics that changed everything. Wholesome as well, a Kansas wheat field, it launched a brand that would far outlast both men’s lifetimes.

Children’s literature would never be the same.

And it was a smash.

A Broadway musical with a reworked plot soon followed. It made both Baum and Denslow rich men, although an ugly battle over just who was most responsible for the Oz success eventually split them apart.

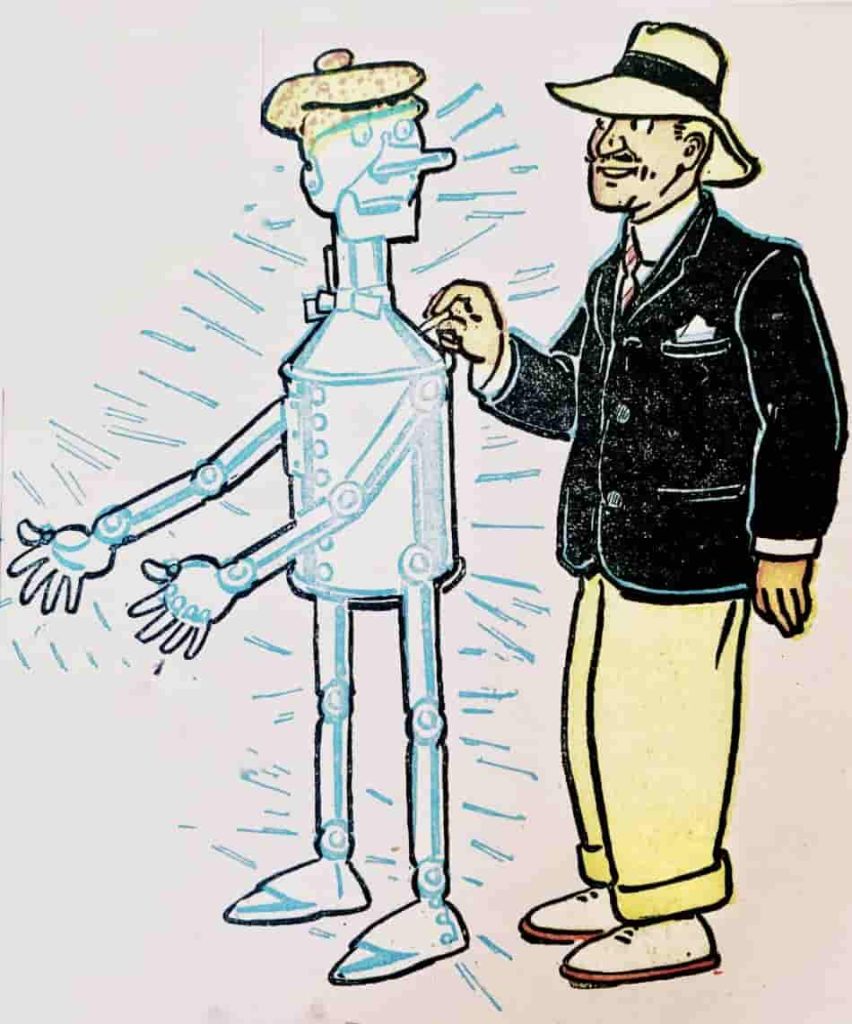

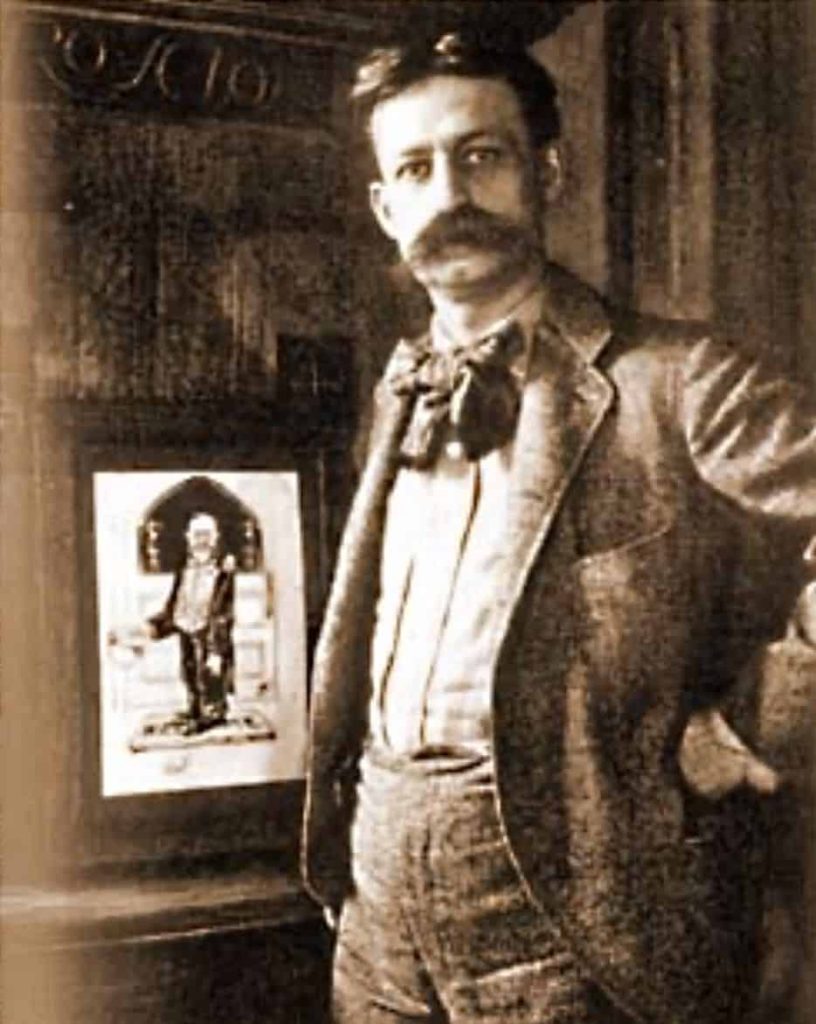

William Wallace Denslow, the famous illustrator — he with the bushy mustache, the booming voice, and the snappy attire — needed a place to reset.

He found that spot in Bermuda.

“You ask me why I like Bermuda,” he wrote in a Buffalo newspaper in 1909. “It is because it is not only the most beautiful spot I have ever found, but also the most healthful.”

Paul Henry Doughty, a Bermuda maritime historian and artist, grew up on a 44-acre farm in Paget, one of the island’s nine parishes. His grandfather bought the land in 1910, seven years after Denslow first sailed to the island.

“In Denslow’s eyes, the landscape of Bermuda would have been thick jungle, then an open field with lilies in it, things like that,” Doughty said. Travel was by donkey- or horse-drawn wagons, the manure along the muddy roads attracting swarms of sparrows.

“There was a saying, I don’t know when it started, the Bermudians used to say, ‘Come to Bermuda, the land of sunshine and flowers, horse shit and showers,’” he said.

For artists at the turn of the 20th century, Bermuda was still just raw enough. It made an impression for those looking for an escape or a sanctuary. It could be an out-of-the-way place to show off your wealth, to promote your art, or to even spin a little made-up magic.

It’s where Denslow, at age 47, came at the top of his career, when all things seemed possible.

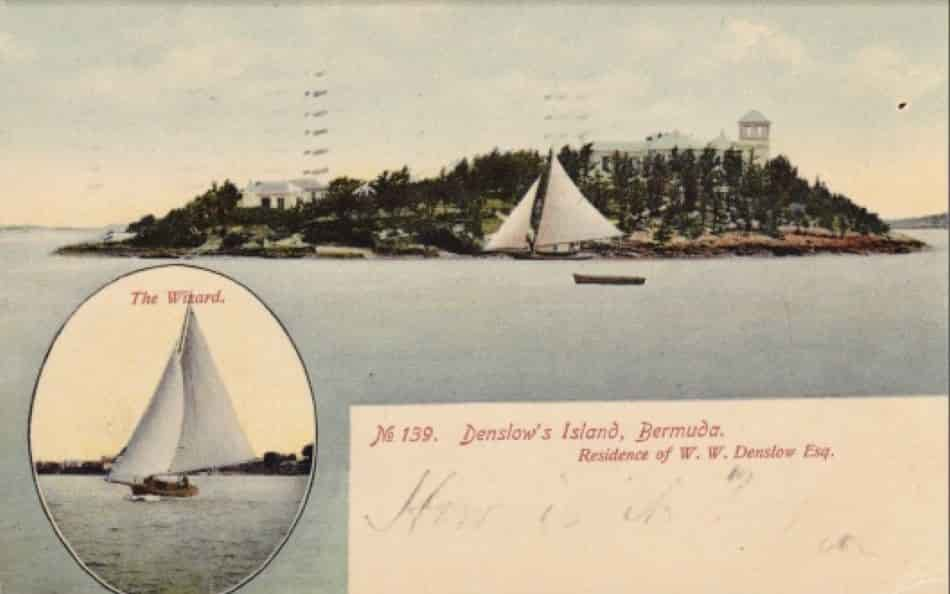

But he didn’t just sip tea in the tropical winter shade. He took part. He built a fairy tale house with a turret. He raced his Bermuda-built boat, named (naturally) The Wizard. He took inspiration from the kaleidoscope of island color and made new art.

And it was here that he crowned himself King Denslow I.

He actually did that.

“He was bonkers as you can tell, but in quite an amiable way, obviously,” Hodgson said. “He was great good fun. And Bermuda fired his imagination. So he wrote this book and the concurrent musical about the island and Bermuda was in it and had it worked it would have been great.”

It was a brief landing — Bermuda sojourns can be that way sometimes — but Denslow’s time on the island would mark him for the few remaining years of his life. He told stories about it. Lots of them. And the Bermuda connection appeared prominently in his obituary, the island escapade being one of the defining aspects of his life.

It was part of who he was.

Denslow meets L. Frank Baum

Denslow was just 14 years old when he began his art studies, a student at two different New York City academies, according to his 1976 biography, W.W. Denslow by Douglas G. Greene and Michael Patrick Hearn. (Despite these connections, he was largely self-taught.) At 16, desperately poor and practically on his own, he sold his first illustration.

His subsequent career led him to crisscross the country, working for newspapers in Chicago, San Francisco, and Denver — a freelance artist and newspaper reporter going wherever he found work. At one point, according to his biography, he took a few months off to become an honest-to-goodness cowboy in Colorado.

It was apparently harder for an East Coast boy to pull off than it looked.

It wasn’t until he returned to Chicago, according to Greene and Hearn, that he shed his credentials as a simple newspaper artist.

Beginning in 1895, Denslow turned to designing posters and theater costumes, the authors wrote. As his reputation grew, he evolved into the somewhat fanciful character of his later career, that being Hippocampus Den with his trademark seahorse signature totem.

Then, in 1896, Denslow met L. Frank Baum, an ambitious writer of children’s verse, at a meeting of the Chicago Press Club, according to his biographers. After they began working together on some projects, Denslow decided he would focus on illustrating children’s books. Soon after, in 1900, came Oz.

For the first time in a life spent working from job to job, Denslow had money to spare and a best-seller on his hands.

He was exhausted.

Denslow’s Bermuda Landing

Elise Outerbridge, curator and director of collections at the Masterworks Museum of Bermuda Art, said the island has always been a place for artists of a certain means to spend their wealth in the sunshine, a short winter jump from “frost to flowers.”

“It was also a respite for a lot of people,” she said. “I mean, there wasn’t much else to do. It was calm. It was tranquil. It was interesting for artists and writers because it wasn’t Florida. You didn’t have to take the train. But it was exotic enough. It seemed to appeal to that kind of Bohemian mind.

“Many artists were wealthy and came from wealthy families and loved to espouse the idea of plein air painting, something that worked better in Bermuda than the East Coast in winter.”

And it was away from the noise, something that was surely appealing to Denslow following the success of Oz.

“(F.) Scott Fitzgerald came down here with Zelda and finished Tender is the Night. Eugene O’Neill found a lot of comfort here. There have been writers over the years who came because (in Bermuda), you’re not in the midst of cacophony. Some people like it, some people don’t. Some people need the cacophony. It depends on the person.”

Bermuda was famous for its famous visitors before Denslow and his Oz vibe arrived in 1903.

Those first arrivals— Mark Twain, Winslow Homer, Frances Hodgson Burnett — are part of Bermuda lore.

In those early days and later, artists, writers and soon musicians came to the islands for peace, health and sunshine. And to be, well, away. Away from the crowds, the press, and the demands of celebrity. And in the case of one future American president, his wife back in the States. That would be you, Woodrow Wilson.

It had begun a few years earlier when Queen Victoria’s daughter, Princess Louise, arrived in the winter of 1883. In her extended, very private stay, she sketched and painted the island, calling it “a place of eternal spring.”

The feeling stuck.

Tom Butterfield, founder and creative director of Masterworks, said the princess’s Bermuda stay set the stage for the creative types who would arrive later.

“That’s been my whole take of what I’ve been trying to get people to understand time and time again. The idea that the muse of the island served writers and served photographers and served painters and served sculptors and, more recently, it served musicians like John Lennon and even David Bowie.

“It’s all fit and fiddle to me about this little fleck of sand that has had such universal acceptance as a place to hide and hush and to find solace and everything else.”

By 1890, Bermuda was “known as a haven for well-to-do Americans” there to enjoy the winter society, according to Another World: Bermuda and the Rise of Modern Tourism by Canadian professor Duncan McDowall.

(The swarms came later. Between 1908 to 1912, a still unregulated Bermuda tourist industry led to a boom in visitors, driven by the increase in cheap steamship runs. It taxed the island to overflowing with some visitors sleeping under the stars at Victoria Park in Hamilton, according to McDowall’s 1999 book. This prompted island leaders to reconsider just what type of visitor they wanted to attract.)

Would Bermudians have welcomed Denslow to the island?

“Of course,” Doughty said. “They would welcome any person who was wealthy because they’re going to sell him stuff.”

Bermuda Tall Tales

Denslow doesn’t figure as prominently as other celebrity guests in the studies of early Bermuda tourism. But that doesn’t mean he isn’t remembered. Some tales are more probable than others; some may even be true.

For example, his sailing prowess.

According to local newspaper archives, Denslow participated in many yacht races against local wealthy families in his Bermuda-made sloop, The Wizard. His sailing became part of that Bermuda persona he sold to newspapers back in the States.

“Since taking up a residence in the South Seas, Mr. Denslow has become quite a yachtsman, and he glories in the fact that his 50-foot sloop has won many prizes in the contests about the Bermudas, and is yet to be defeated,” proclaimed one news report.

“The sloop is called The Wizard and is branded with a huge hippocampus (or seahorse) on both bow and stern.”

His success, however, was certainly overblown. Although competitive, according to accounts in The Royal Gazette, The Wizard chalked up several defeats. To be fair, it would have been difficult to break into the tight yachting society of early 20th-century Bermuda and its ambitious sailing families.

Still, the winning yachtsman was one piece of the island artist role advertised by this savvy self-promoter. He knew how to spin a yarn.

Denslow wrote about Bermuda, talked about Bermuda, and sold Bermuda. He put it in his art and embraced it in his lifestyle.

Again, that color.

“The white houses nestle among the dark green cedar trees and give a contrast to the landscape,” he wrote many years later, “while the sea of gorgeous variated light greens, blues and dark browns, where the coral reefs come near the surface, forms the most striking foreground, and the deep blue of the sky completes the picture.”

A short-lived comic strip with Oz characters made a visit to Bermuda; in a children’s novel, the plot (incongruously) finds its way to the island. That novel he turned into a “musical extravaganza” meaning that for a brief moment anyway, Bermuda shone in the footlights of Broadway.

Denslow may never have recaptured that Oz magic, but in Bermuda, he found a place to test out some new ideas, to partake in its tropical bounty, and to have a little fun.

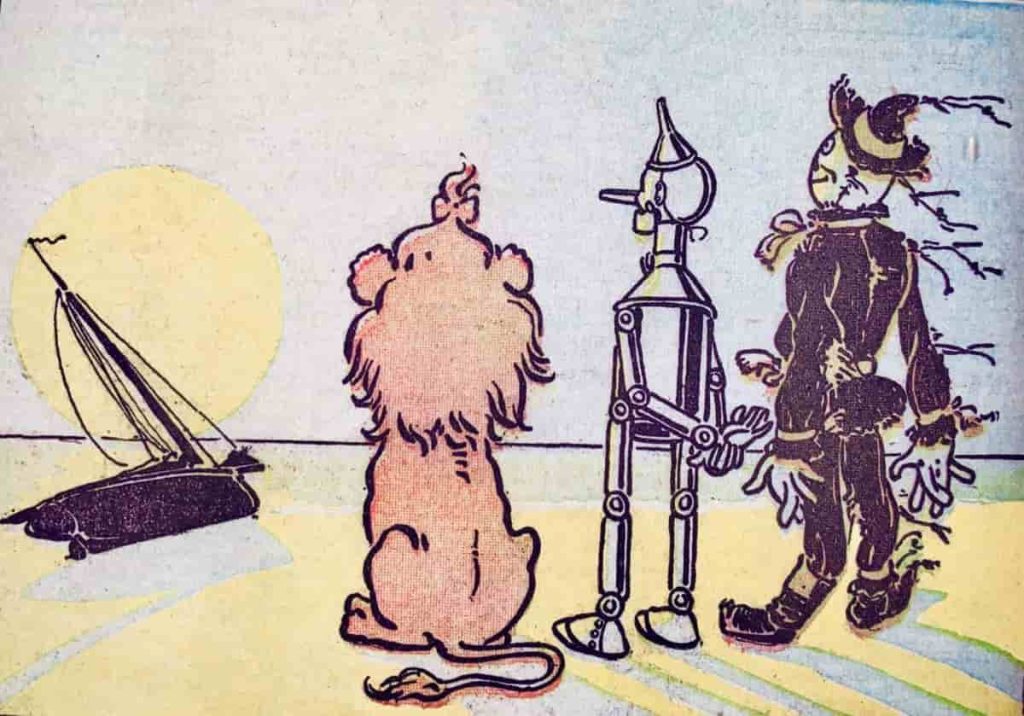

The Scarecrow, the Lion and the Tinman were walking one evening on the beautiful beach of the South Shore of Bermuda, just as the great round moon rose and sent a glittering path of silver across the water.

Denslow’s Scarecrow and Tinman Shipwrecked — February 5, 1905

The Pearl and the Pumpkin

Mark Twain wrote in 1877 that “Bermuda was the right country for jaded man to loaf in.”

For all his quirks, Denslow was not a loafer. Not that he didn’t like fine things, such as a nice cigar and a beautifully bound book to decorate his shelves, as his biographers noted. And his Bermuda experience included much self-made luxury.

But he was a working artist, there to build on a career at its height.

“You ask me what I know about Bermuda,” Denslow recalled in a newspaper piece several years later. “I do not know all of Bermuda, yet have tramped it from end to end, have ridden over it through all its roads and …. through intricate passages of the reefs that surround it.”

Bermuda images appear in the undersea adventures in The Pearl and the Pumpkin, in the elaborate scenery in the stage production, and in the yellows and blues in the comic strip’s ocean voyages.

His embrace of the water wasn’t new. Denslow had been a lover of boats since he was a child growing up along the Hudson River in northern Manhattan, according to his biography.

In a magazine article at the time, a friend described the artist’s sea voyages to North Rock, a coral reef seven miles north of the main island. It’s where he discovered “those wonderful submarine effects that you see” in the stage version of The Pearl and the Pumpkin.

“Thirty feet under the water did he go, and the rocks, the vegetation and the (ship) wrecks are almost an exact reproduction as he saw them when he was down there,” according to the article.

“In order to get the proper coloring, he painted while swaying in a small boat, his helpers holding water glasses over the surface to prevent ripples.

“If you could see the ordinary tempestuous state of the water at this spot, and the dangerous formation of the reefs, you would understand why it was such a hazardous undertaking.”

In The Pearl and the Pumpkin book, Denslow wrote of a magical undersea world, which he would have seen in the depths at North Rock:

As they crossed the portals, Joe stopped, dazzled by the beauty of the scene. If the outside palace was gorgeous, there were no words to describe the interior. They were in a great hall, formed by countless arches of pink, green, white and yellow coral, through the pillars supporting which shone a soft light that made the walls, ceiling and floor glitter like diamonds.

Denslow’s guide on these North Rock explorations was Bermuda pilot Joe Powell.

For generations, black and Native American slaves and freed men had guided vessels through Bermuda’s dangerous reefs and narrow channels in their native cedar gigs, according to history compiled by the National Museum of Bermuda. In later days, pilots like Powell led visiting steamships safely into dock and took early tourists on sightseeing sails.

“Few white men there are in Bermuda who can take a boat through the reefs to North Rock,” Denslow wrote of Powell’s sailing skills. “They navigate them at night, in change of weather, in fact, at all times. The difficulties are something hardly explainable.”

(In 1929, when a ferry accidentally sunk his vessel, The Royal Gazette described Powell as an “old sailor and proud of his boat,” which he had used for taking visitors on pleasure trips around the island.)

Denslow’s Bermuda experience was not always paradise or even a fairy tale. The artist had disagreements with workers at his house, a possible early sign that the island experiment was destined not to last. One worker even took him to court over money owed, according to local newspaper archives.

Still, for a brief time, the blue tropical skies appeared to be just what he needed.

An Island Adventure

Less than a month after he arrived in Bermuda in 1903, Denslow wrote to a literary journal back home about his island adventure. It contained a bit of that Den bombast, which in real life sounded like “the voice of a second mate in a storm — a fog horn voice,” a colleague would remember.

“The climate of New York was too rich for my Western blood, and I had to steer for sunnier climes, so I am here in the land of the lily and the onion, the picturesque land of coral houses, white against the dark green of cedar trees, and the land of vivid, brilliant color,” Denslow wrote.

Was it a role play? Like being a cowboy? Something to broadcast to the world? Here I am on my island? A king, no less?

Yes indeed. But beyond the horn-blowing, something else happened.

Bermuda won him over.

“He liked sailing and he really lapped up the atmosphere there and that’s what influenced his work. (The) Pearl and the Pumpkin takes place in Bermuda. It’s starts off in New England, but ends up in Bermuda. And he also sends the Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman to Bermuda in his comic strip. He really enjoyed being there,” said biographer Michael Patrick Hearn, in a telephone interview last year.

A Place for Artists in the Atlantic

No one knows for sure who planted the idea of traveling to Bermuda in Denslow’s mind. Hearn said it could have been Elbert Hubbard, founder of the Roycroft campus, an arts and crafts community in upstate New York, where Denslow was a contributor.

It also seems highly possible that Denslow knew of landscape painter Winslow Homer’s two Bermuda trips, which took place between 1899 and 1901. Homer was a nexus for artists coming to Bermuda. In this case, the timing is almost exact.

At the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo in 1901, Homer showed 21 watercolor paintings of Bermuda and the Bahamas. It was a prestigious months-long event, a showcase for artists and thinkers alike.

On Jan. 6, 1903 — two years after Homer’s last trip — Denslow first arrived in Bermuda, traveling with his then-wife Ann on the steamship S.S. Trinidad, according to a passenger list published a few days later in The Royal Gazette. Also traveling with the couple was their friend and children’s author, Grace Duffie Boylan.

The ship — built to carry 170 first-class passengers — was a refitted freighter designed to accommodate the growing New York-to-Bermuda winter tourist crowd.

“Bermuda is paradise, but you have to to through hell to get there,” Twain once said of the choppy sea journey from the East Coast to the island in his day. Apparently, the newer and bigger ships built by the Quebec Steamship Co. didn’t completely obliterate that experience.

In a tongue-and-cheek newspaper account a few weeks later, Boylan described the difficult January sea journey, possibly tweaking Twain.

“Bermuda may be read ‘Paradise,’” she said, “but the stranger gets well shaken up and humiliated before he gets there.

“Sea sickness as an experience is not be be altogether condemned. It entirely removes all fear of death, annihilates pride and favoritism and reduces the complex relationships of society.”

Among the 50 women on board, the only one not to get sick was Ann Denslow, she said.

“She weathered the fiercest part of the storm on deck with her husband, and came with the spray shining in her hair, to read to pale little children and to comfort the other sufferers with funny stories,” Boylan wrote.

A Land of Vivid Color

Soon after his arrival, Mr. Denslow was already touting the bounty of Bermuda to readers back home. In a published letter dated February 3rd, he gushed about the glorious Bermuda sunsets.

“Returning after a day’s sport at eventide, you would think, on entering this most beautiful (Hamilton) harbor, that the houses were all gilt-top, but this effect is merely produced by the setting sun upon the white vellum binding peculiar to this place,” Denslow wrote of the limestone roofs unique to the island.

“It is no wonder that my wife and I, who were pretty well rundown, are improving immensely and feeling better each day.”

Always looking one step ahead, Denslow also noted that he was busy creating his next blockbuster.

“I am trying a rather big piece of work, but with the aid of the genial climate will be able to bring it through,” he said.

The Denslows stayed that winter at the Inverurie Hotel on Hamilton Harbour, a handy spot for boating expeditions. The artist was already finding color: an angel fish “in bright blue levant with elaborate gold tooling of unique design” and a lobster colored like “marbled end paper.”

Career-wise, it was a very productive stay. He began work on his 18-volume Denslow’s Picture Book Series — a collection of original and reworked fairy tales.

(One critic chided “the moral tone” or the scrubbing clean of the traditional fairy tales in the collection. For example, in “Little Red Riding Hood,” the wolf is only meant to scare the girl, not to eat her.

“Your pictures are splendid, but your stories ‘ain’t true,’” said the reviewer.

On the whole, Denslow found these old tales too frightening for young children. It’s a view that influenced his children’s stories, including the decidedly not-too-scary plot of The Pearl and the Pumpkin.)

Whatever the relative success of this first Bermuda trip, it was not enough to save his marriage. Both he and Ann were already in love with other people. She filed for divorce in September, just a few months after that rocky steamship ride full of seasick passengers.

By next winter, however, Denslow had a new bride and even bigger plans. An island fancy was about to turn into something more. Something royal.

Upon its back leaped the Canner still holding the Dodger in his grasp, and cried to the shark,

‘Bermuda, as quick as you can possibly swim!’

The Pearl and the Pumpkin — 1904

Enter King Denslow I

Three months after his divorce from Ann, Denslow married a woman he had met during his 1902 stay at Alma Springs Sanitarium in Michigan, a spa that advertised its healing bromide waters.

In a 2015 article about Denslow’s Bermuda experience, Jane Albright, president of the International Wizard of Oz Club, wrote that the artist had suffered a nervous breakdown, prompting his stay at the spa. Denslow had also complained of a nervous prostate and rheumatism.

“The other woman” from the sanitarium was Frances G. Doolittle of Chicago, “a 32-year-old widow with two children and considered wealthy,” according to the article, which appeared in The Baum Bugle, the club’s magazine.

The wedding announcement hit the newspapers a few days late because, according to one colorful news report, “Mr. Denlsow put the marriage notice into his pocket after the ceremony and forgot about it.”

The newlyweds left for Bermuda two weeks later, almost a year after Denslow first arrived with Ann, to spend the winter and their honeymoon.

As he had so many times in his life when things didn’t work out precisely as planned, Denslow was starting over.

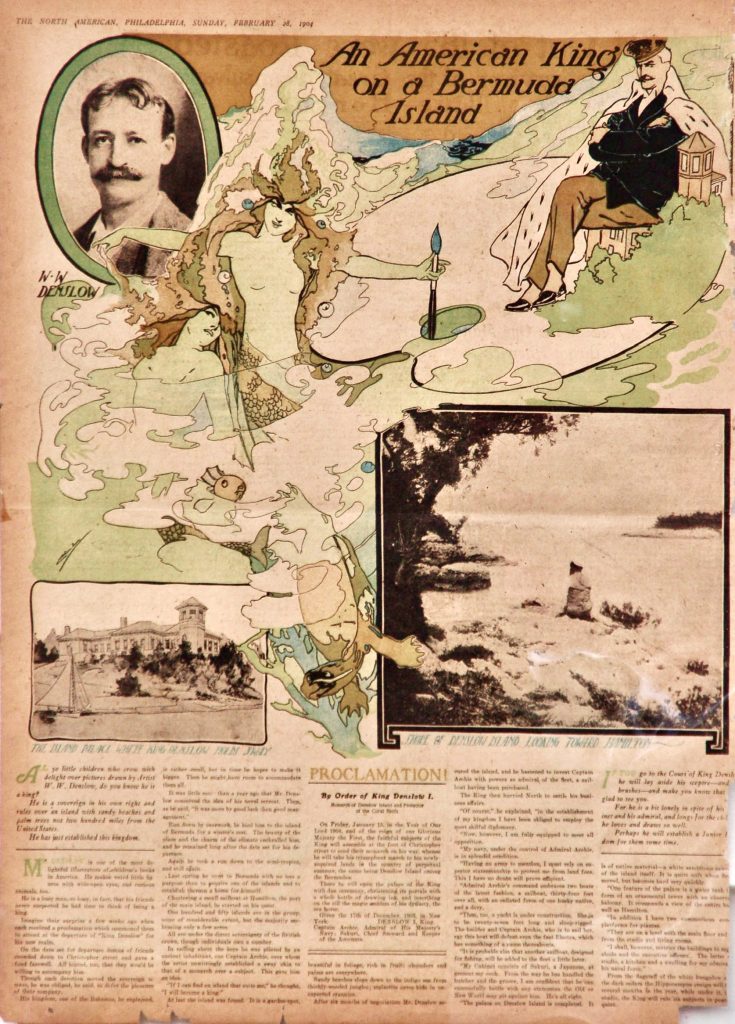

All ye little children who crow with delight over pictures drawn by artist W.W. Denslow, do you know he is a king?

He is a sovereign in his own right and rules over an island with sandy beaches and palm trees not two hundred miles from the United States.

He has just established this kingdom.

— The North American (Philadelphia newspaper) — February 28, 1904

And so it began

To launch this ambitious new phase of his Bermuda enterprise, the artist sent invitations for friends to join him as he set sail for his “new realm.”

This time, Denslow boasted, he intended to lay claim to one of Bermuda’s small harbor islands. He would rename this new territory, appropriately enough, after himself.

He would be: “An American King on a Bermuda Island.”

His “proclamation,” published in newspapers across the United States, went like this:

“By order of King Denslow I, Monarch of Denslow Island and Protector of the Coral Reefs, the faithful subjects of the King will assemble at the foot of Christopher Street (in Manhattan) to send their monarch on his way, whence he will take his triumphant march to his newly-acquired lands in the country of perpetual summer, the same being Denslow Island among the Bermudas.”

That’s right. An actual island. A slice of the Emerald City in the Atlantic.

On top of that, he hinted that an extravaganza was on its way to rival the brilliant colors of Oz, inspired by his discoveries in the jeweled Bermuda waters.

He wrote that winter that he had already “found a crimson which fills him with joy in the flannel-mouthed grouper, a fish with a mouth like a coal shuttle and a color unrivaled in any dye pot.”

Would it last?

Friends were already lining up to predict the entire kingdom operation amounted to nothing more than a house of cards.

“There are glorious possibilities for dreaming, but little incentive for work on Denslow’s Island, and the artist’s friends prophesy that he will return to New York to put on paper the visions that he sees in the Bermudas,” according to one skeptical newspaper piece.

Denslow had found his island the previous spring, he told the press. The “quest” began after chartering a boat out of Hamilton, the main Bermuda port. The pilot, “an ancient inhabitant, one Captain Archie,” guided the search.

“If I can find an island that suits me,” Denslow said, “what’s the matter with making it a kingdom and establishing myself as king, with a select population of subjects? I’ll do it.”

He found what he was looking for in The Great Sound, a small piece of paradise called Dyer’s Island.

“It is a garden spot, plenteous in foliage of the most beautiful kind, oleanders and palms predominating. Sand beaches slope down to the blue ocean from thickly wooded spots; caves of stalactite are found in the most unexpected places, and everything is at hand to make the ideal retreat of which Mr. Denslow dreamed,” sang the full-page announcement.

Now, as a finishing touch to his tropical fairy tale, Denslow began work on his castle.

His plans were to use native Bermuda white stone to build “an ornamental tower with observatory balcony that will command a view of the whole Great Sound, the bay and Hamilton,” he touted in a newspaper that January.

“Living out of doors as much as one does there, these will supply very great comfort, and an agreeable change to one who has tasted the sharp air of late fall and early winter of New York.”

(It’s possible that Denslow got the idea for his prominent tower from a similar one near the Royal Hamilton Dinghy Club. He would likely have seen the Walford House, built in 1892, from the water on one of his boating expeditions the previous winter.)

Denslow made his island guide Captain Archie “admiral of his fleet,” which would include a Bermuda-made cedar yacht already under construction.

Glorious Possibilities for Dreaming

Even today, more than a century later, people in Bermuda talk about the Oz artist in his white tower overlooking the sparkling harbor, writing his fairy tales.

From his turret, Denslow would have had an unencumbered view of Bermuda’s spectacular golden sunsets.

But this front row seat didn’t inspire the Yellow Brick Road or any other magical Oz image, as is sometimes claimed. The timing isn’t right, despite the numerous shout-outs by tour boat guides over the years.

But the tales, true or false, are the legacy of Denslow’s Bermuda experience.

Hartley Watlington, whose family owns a tiny 130-meters-long island immediately east of what was Denslow’s Island in The Great Sound, heard the stories from his grandfather.

John Hartley Watlington, was an avid canoeist, who founded the Pitts Bay Canoe Club. He and his friends would canoe to various islands to picnic. This included what would later become the family’s own Watling Island.

“Denslow liked to work in the tower on his island house when it was nice and sunny and not too windy,” Watlington said his grandfather told him. “It is a nice view from up there. It was before they had the stairs. He had some sort of rope ladder that he would use to get away from his wife and be alone to work.

“When Denslow was up in his tower with his sunglasses on, working, one of these picnics on the island just opposite became his Emerald City for The Wizard of Oz.”

Stories that stay.

One thing is for sure, with its views and wild lilies and no one else around, it was an enchanted setting, Doughty said.

In the early 20th century, when Denslow and Frances lived there, the island had no electricity. Just before sunset, a man rowed out to light a lantern filled with whale oil. And that would like be the island’s main illumination.

“Can you imagine that island under the moonlight?” Doughty said.

“You don’t realize how magical (the harbor islands) are until you’ve been on one. Any one of those islands in that group. You go out there when nobody else is around. They’ve got this feel about them that is different.”

In concluding his proclamation, Denslow predicted a glorious reign on his new island:

“From the flagstaff of the white bungalow among the dark cedars the Hippocampus ensign will flutter for several months in the year, while under it, in the studio, the King will rule his subjects in peace and quiet.”

The successful artist nowadays finds it well worth his while to leave his studio and study first-hand a world that is full of a number of things.

The Los Angeles Times — January 31, 1904

The Yellow Brick Road

Mark Twain, Bermuda’s most famous early visitor, arrived exhausted in 1868. He returned throughout his life, the last time just weeks before his death in 1910.

(It’s unclear whether he and Denslow ever met in person, although Denslow illustrated his novella, The Million Pound Bank Note, in 1893. Denslow also offered to sell Twain his Bermuda island at some point, Hearn said.)

Yet for all his devotion to Bermuda, Twain never used the island as a backdrop for his stories. That would have ruined it.

“It was too close to his own ideal of a fantasyland to tamper with, so he simply reported his ‘rambling notes’ of the place. In Bermuda, there was nothing to escape from,” McDowall said in his history of Bermuda tourism.

But Denslow did both. Sang the charms of the island to the press back home and included it in his work.

For a short time at least, thanks to that well-promoted kingship, Bermuda dazzled in words and on stage.

It was a good story. Denslow made sure of that.

“It was the best place for him to work. He found it most congenial to working. He really enjoyed being in Bermuda,” Hearn said in an interview.

One of the first tales he told was about his cat, Bob, who was involved in an early mystery at Denslow’s Island. It included a brush with Bermuda’s darker history, that being modern-day pirates.

Initially charged with ridding the island of rats, Bob got into a bit of a scrape with a worker helping build Denslow’s house. This worker, the artist wrote, “looks like a pirate of the old school, (and) according to all accounts, used to be a wrecker.”

In Bermuda history, this would be someone who lured off-shore boats into the island’s dangerous, reef-filled coastal waters to cause a shipwreck. The “wrecker” would then pillage the spoils.

Denslow wrote that this man told him he was the “good sort” of wrecker, whatever that meant.

The story went that the worker, also a fisherman, had placed an eel pot by the island dock. The bait repeatedly and mysteriously disappeared. After a stakeout, the culprit was found to be Bob, who was swimming off the dock and dunking underwater to steal the bait.

“He is now a great pet in the Denslow household, and is famous all through the Bermudas as ‘Bob the Fisherman,’” Denslow told the newspapers in late 1904.

See these islands dotted about so handy, said the Scarecrow, and notice on yonder shore, the dark green, dimpled here and there with white houses, the opal sky above, the deep blue and emerald green of the sea below, which all go to make a picture of enchantment.

Denslow’s Scarecrow and Tinman in Bermuda — January 29, 1905

A Good Story

Denslow’s Island, or Buck’s Island as it is called today, is one of 181 in the Bermuda archipelago.

Although Denslow initially trumpeted that he had bought the island — see that proclamation — he at first only rented it, beginning construction of his house before the sale went through.

Like today, Bermuda had restrictions against expats owning property, something Denslow somehow found his way around.

The island was also much smaller than Denslow first proclaimed, a total of four versus ten acres.

When he was finally able to buy it in 1910, he had to borrow money from a friend, composer Paul Tietjens, to complete the deal, according to Greene and Hearn’s biography.

In some respects, it was the perfect time to try something big.

Oz in the Comics

Because he shared Oz royalties with Baum — a point of contention between the two — Denslow continued to receive money from The Wizard of Oz musical for eight years. He had helped design the costumes of the Tin Man and the Scarecrow for the show, but otherwise was not intimately involved.

For the first time in his life, he had money pouring in, giving him the freedom to try new things.

So, for a brief time, Denslow wrote a newspaper comic strip featuring the Oz characters, competing head-to-head with another strip of Oz adventures by Baum. Because of that shared copyright, both men felt they had the right to use those characters in other works.

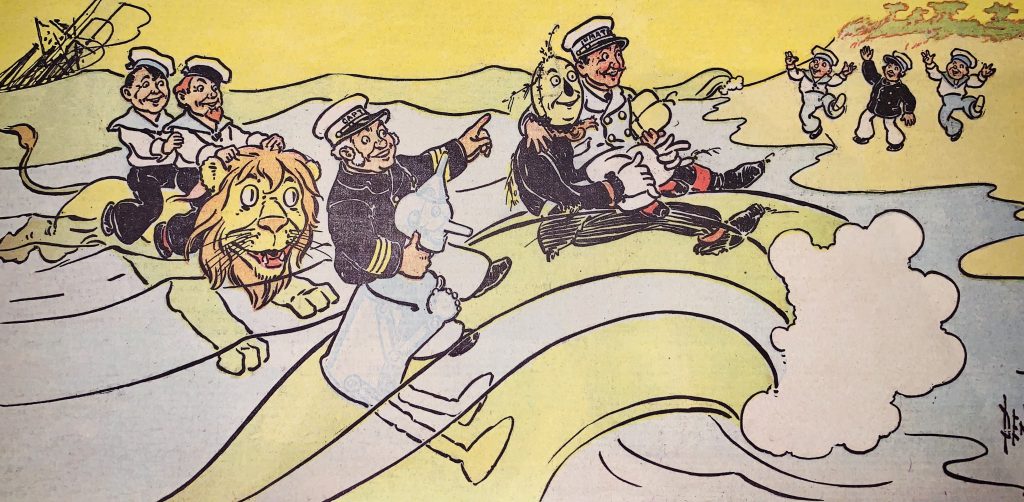

Denslow’s strip, which began in late 1904 and continued for 14 weeks, included a side trip to his new island home, bringing the Scarecrow, the Tinman and the Lion to play on Bermuda’s pink sands:

As the good ship swung up to the dock in Hamilton, a joyous shout went up from the crowd on shore when they saw the Lion, the Scarecrow and the Tinman upon the upper deck, and in answer the three raised their hats in greeting.

Denslow’s Scarecrow and Tinman in Bermuda — January 29, 1905

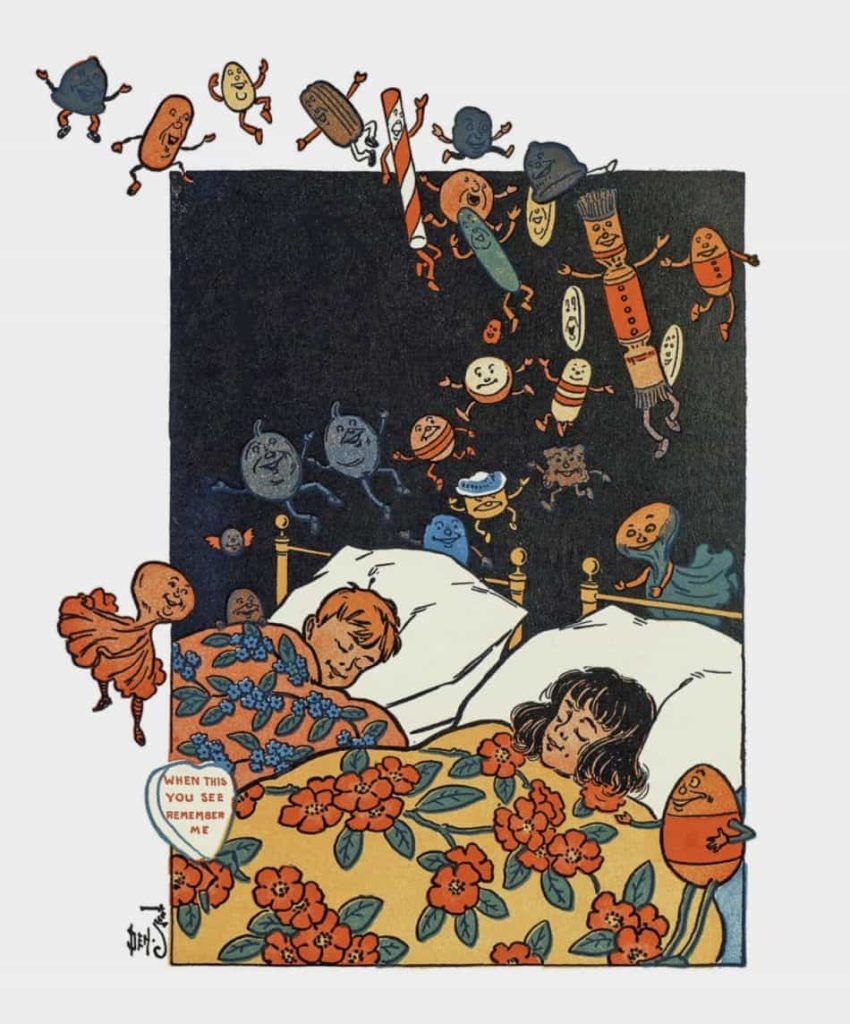

The madcap visit, played out in newspapers across the country, was told in bleached primary colors and, in classic Denslow style, features characters spilling out of frames to portray motion.

(One strip in the series contains a tucked-away self-portrait of Denslow as the ship’s captain, possibly a nod to his trumpeted prowess as skipper of The Wizard.)

As the heroes disembark from the steamship, a Bermuda customs officer asks the Scarecrow, “Have you any cigars or liquors concealed in that straw?”

The strip includes an illustration of that officer pulling out the Scarecrow’s innards in search of those cigars or liquors. This may or may not have mirrored a similar experience endured by the cigar-smoking and liquor-drinking Denslow on one of his Bermuda arrivals, albeit not as physically intrusive.

The comic strip, however, was a short-lived project for Denslow. The artist had his sights on bigger things than the newspaper funnies.

For starters, there was to be a new book, which “is original in plot and treatment in every particular, and departs absolutely from the scheme of any previous story written for children,” according to a newspaper article in late 1904.

So not anything like Oz, a journey by children through magical lands, notwithstanding.

A Spectacle to Rival Oz

The Pearl and the Pumpkin would be Denslow’s own follow-up to the Oz magic. Something even more spectacular, he promised.

He teamed up with Paul West, a journalist and lyricist, to write the plot, which takes place on Halloween night. It opens in Vermont and with plenty of twists and turns, finishes in Bermuda.

Even before its October publication, the book was under contract to be turned into a musical by one of the leading producers of the day, Klaw & Erlanger. A promotional piece in the US newspapers that July played up its Bermuda inspiration.

“The characters and plot . . . were gathered for the salt-laden atmosphere by Mr. Denslow while sojourning at his island home in Bermuda,” according to one article.

Bermuda scenes dot the text of the book, although mostly as background.

North Rock — “a flat reef with fantastic pinnacles” — appears as Denslow would have seen it on one of his ocean voyages with pilot Joe Powell, before rising sea levels over the next century buried much of it underwater.

His palace on Denslow’s Island appears in the background as does Gibbs Hill Lighthouse and other Bermuda landmarks. The artist also includes fanciful ocean characters, such as bluefish as doormen, mermaids as actual maids, and seahorses as horses. All illustrations are stamped with “Den” and his trademark hippocampus.

Two farm children, cousins Joe and Pearl, are the main characters. (While she is Joe’s innocent companion in the book, Pearl is more of a lovelorn sweetheart in the ramped-up musical.) Famous nautical figures of myth include Davy Jones, the Ancient Mariner and Mother Carey, an under-the-sea fairy godmother.

Although it features 16 full-page illustrations, the dominant color of the book is by far a limited range of orange.

The plot —- something critics of the musical would remark upon later — was less then delightful. Also a little convoluted.

What’s the Plot?

In nutshell, Joe holds a prized secret for growing pumpkins. When he runs into some mischief makers of the nautical variety on Halloween night, an errant wish turns him into a pumpkin.

This somehow leads him and Pearl from the pumpkin fields of Vermont on an underwater adventure to Bermuda, full of the aforementioned fairies and sea creatures. (An “indefinable process” as a reviewer of the musical later opined.) This plot is neatly resolved when they get to the island.

It is Mother Carey who points her wand at the sea while a strange object rises high over the waves and — like a Bermuda sunset in reverse — turns our hero Joe back into a little boy.

“Pumpkin-head, I command you, in the name of Neptune, King of the Winds and Waves, approach!” said the ocean fairy.

“He wasn’t much of a writer,” Hearn said in an interview. “He was no Baum and Paul West was no Baum either. What people remember about The Pearl and the Pumpkin are the illustrations.”

Bermuda’s Pink Sands

The text of the book is also split from Denslow’s art, something so key to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz where plot and illustrations go hand-in-hand.

Such a disconnect is very much against the rules, said Michael Frith, another famous children’s fantasy spinner, in an interview last summer.

As a boy growing up in Bermuda, Frith spent many happy hours exploring the island’s secret places. His boyhood fascination with Bermuda’s famed Crystal Caves inspired him to co-create the 1980s children’s television series, Fraggle Rock.

The Fraggles — first conceived by the late Muppets creator Jim Henson — were jewel-colored, fluffy-topped puppets who lived in a network of sparking caves similar to those found in Bermuda. It was a dazzling underground universe of friendship and play.

Before helping launch the show, Frith was a puppeteer for Henson as well as a former editor at Random House, where he worked on many books by his friend Ted Geisel, more famously known as Dr. Seuss.

In an interview at his old Bermuda home, which was once painted by Homer, Frith joked that his old cohort Dr. Seuss had lived in California near Baum’s California home.

“He had Frank Baum on his doorstep and I had at least the ghost of Mr. Denslow on mine!” he said.

This was the first time he had seen Denslow’s Bermuda-based work.

“I’m a real sucker for anything that smacks of early Bermuda and particularly with this kind of connection. I think this is wonderful. I love skimming the little bits that you have,” Frith said.

“Oh really! They come to Bermuda in their story! Isn’t that fun!” he said, flipping through The Pearl and the Pumpkin. “This is just really fun! Whether this made it good or not, this is just really fun.”

The illustrations themselves, however, don’t actually create a setting for the characters in the book, he said. A lighthouse here, a sailor with a spyglass. These images are “willy-nilly” and don’t appear in the story.

Artist John Neill and Oz

Frith said his hero is the second Oz illustrator, newspaperman John Neill, whom Baum turned to when he split with Denslow. Neill went on to illustrate more than 40 Oz stories.

While he sees Neill as the better artist, he appreciates that Denslow created the Oz characters in the public’s imagination, and that subsequent illustrators had to follow his template.

“Denslow I find really interesting, and having spent a lot of my life designing characters, I really appreciate the brilliance with which he came up with those characters,” Frith said.

“He created characters that were timeless, inimitable. And we’ve seen many variations of them when people do movies or stage plays or other versions of Oz. People have illustrated the books and you’ve got to come back to Denslow’s basic concepts because they’re so strong. You know, Tin Woodsmen with his funnel hat, the Scarecrow — and all this stuff is just inherent in these characters.

“And so when Neill took over he essentially took those characters Denslow invented and then really kind of made them his own.

“The land of Oz was so brilliantly conceived and Denslow’s characters were so absolutely perfect for them that certainly in all the classic representations of Oz, they are the ones that continue to live.”

To fully appreciate Denslow’s talent, Frith said, it helps to examine his commercial work.

“I find his stuff fascinating. To me he’s more interesting as a graphic artist than as an illustrator. His graphics are really powerful and really compelling and he can do really complex images. And organize them really quite wonderfully well.”

Maybe the story or the material is awkward or cliched, but it is always well designed.

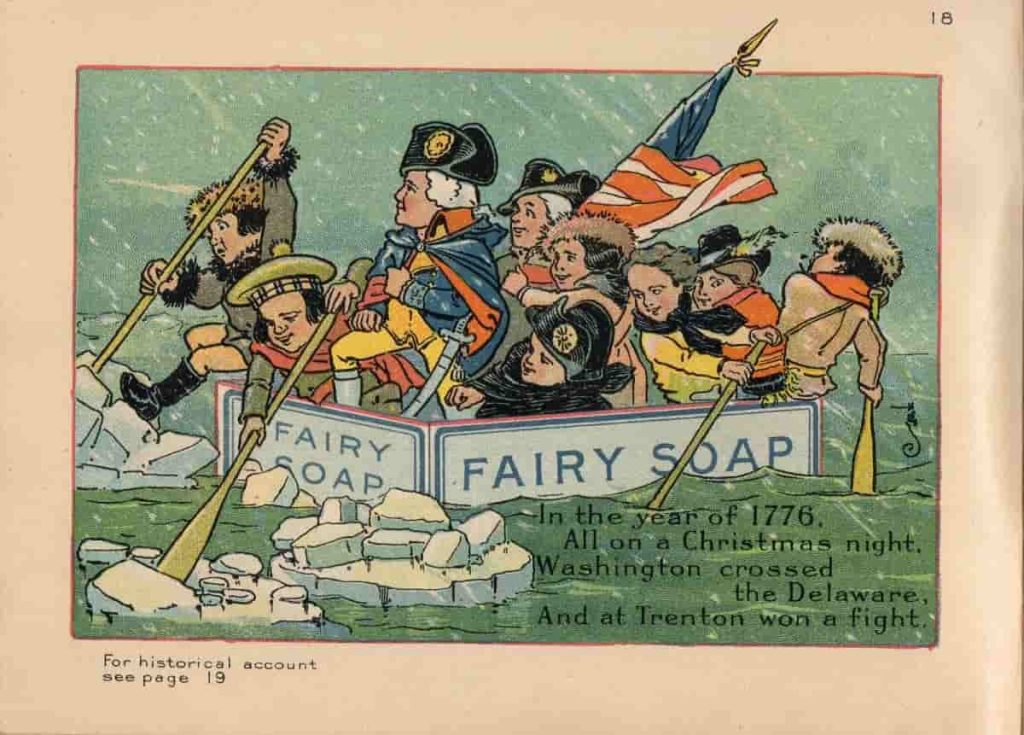

(Note: Here is one example of Denslow’s graphic work of this period, a 24-part history of the United States for Fairbank’s Fairy Soap, published in 1911. Here’s Washington and his troops crossing the Delaware, but as children in a soap box.)

It would have been natural for Denslow to want to take a shot at Broadway, Frith said.

“He did have a certain reputation going in that allowed him to get his foot in the door, which a lot of people didn’t have,” he said. Add to that a market at the time for children’s theater.

And once you’ve got that foot in the door, anything can happen.

“So you can see that people who were imaginative and exciting,” Frith said, “getting into this world of publishing where it was all new and exciting and things were in color … (and you had) mass readership. Then yeah, where does that lead? Ooo that takes you on the stage! Shows! Oh my God, where does that take you? How about radio?!”

Or an Extravaganza

Ah yes. The Pearl and the Pumpkin musical extravaganza. Was it a folly or a natural next step for a successful artist and showman? A leap of faith at a time when big things seemed possible?

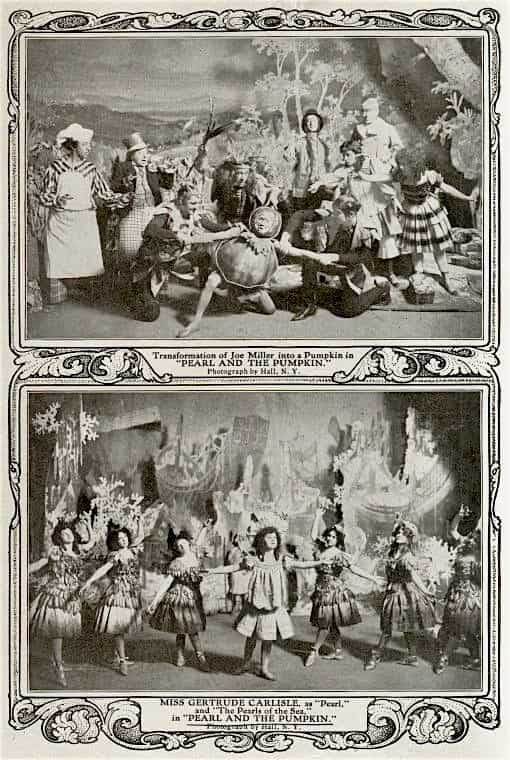

The Pearl and the Pumpkin show opened in Boston in July 1905. At the time, The Wizard of Oz musical — a vastly rewritten production based only broadly on the book — was already three years into an eight-year run.

Oz the musical was the most successful of show of its day, according to The Road to Wicked: The Marketing & Consumption of Oz from Frank Baum to Broadway, a 2018 study of the century-long culture of Oz.

It influenced theater for the next decade and left the public clamoring for the “glow” and “tingle” of the Oz fantasy, its authors wrote.

In other words, it was a boon time for anyone with a similar children’s story. Never mind someone with a direct Oz connection.

Enter The Pearl and the Pumpkin, a children’s fantasy told by the original Oz artist himself, plugging away in his Bermuda castle, hoping for another hit.

The producers, part of a New York-based theater syndicate, put somewhere between $50,000 and $70,000 into the show. (This equates to about $1.5 to $2.1 million in inflated value today.) The cast numbered around 150 people, including a Castilian dance troupe from Madrid, and 24 new songs.

Denslow handled the scenery and the costumes. West contributed the lyrics while John W. Bratton wrote the music.

(Both West and Bratton were established theater collaborators and each had career success. West would later collaborate with Jerome Kern while Bratton had a major hit in 1907 with the “Teddy Bears’ Picnic.”)

Like Oz before it, the plot for The Pearl and the Pumpkin show was juiced up for the stage. Here’s where that ruffled chorus line of Bermuda lilies comes in as well as the very grown-up love interest between Joe and Pearl.

“The locale of scenes of the third and last act is in the beautiful island of Bermuda, the land of the lily, the oleander and the palm, where the native-born tired and the traveler from the ice-bound North, disports himself on the bluest water in the world, gliding over the fantastic coral beds of the shallow reefs,” according to a newspaper piece promoting the musical.

Easter Parade

(A few decades later, those very same Bermuda lilies would inspire another musical number: Irving Berlin’s Easter Parade.

On a visit in 1933, Berlin enjoyed the island’s annual Easter pageant, attended by women wearing elaborate hats topped with tropical flowers. It inspired him to pen, “In your Easter bonnet, with all the frills upon it; You’ll be the grandest lady in the Easter parade.”)

Denslow’s tropical research paid off with at least one keen-eyed reviewer, who noted that a giant lobster in the musical’s submarine scene was colored black, not dinner-ready red.

“They are the creations of some artist who doesn’t assume that theatrical audiences are ignorant or unobservant.”

Initial reviews in both Boston and New York were exuberant.

The night after its Broadway debut in August, The Brooklyn Citizen proclaimed:

“Its maze of beauty, of color harmonies in brilliant stage pictures, and magnificent and tasteful costumes, is consistent with its pretty, catchy music and altogether lively and interesting entertainment.”

And while “the story begins nowhere and doesn’t get far from it,” the scenes, the dancing and the “amazing brilliance” makes you forget.

But that brilliance didn’t save it. Maybe it was “the plot of fanciful conceits” as another review pointed out.

The show closed three months later after 80 performances in New York, according to the Internet Broadway Database. It did better on tour, Greene and Hearn wrote, running for several months, although at a rumored $55,000 loss for producers.

It just didn’t work.

A Little Too Much?

Hodgson said he wonders if Denslow had overshot with his elaborate Broadway extravaganza, and in the process, squandered away all his Oz capital.

He points to the excesses of The Pearl and the Pumpkin show that included a full-scale reproduction of North Rock.

“The sets were incredible and these people flying around on seahorses and they spent a fortune on it. I assume the lawyers said, ‘Look, the story is too close (The) Wizard of Oz, blur it here, blur it there.’ Well they did and nobody understood it,” Hodgson said.

“The tragedy of Denslow is his ego. Instead of sitting back and — I mean Jesus Christ! He was made for life. But he was jealous of Baum, he was jealous of Baum getting the headlines. I mean my God. He worked in the media. He knows it’s all make-believe. Just accept that the only byline that matters is the one on your check, mate.

“I think it’s awful. He should have died a millionaire out there” on his Bermuda island.

“He was hoping for lightening to strike twice. It’s not that simple. And he wanted to get out from under Baum’s shadow. I assume he felt, ‘Well I don’t need him. I can do it by myself.’ But he didn’t get the right associates. He certainly didn’t get the right storyline. And that was that. He was broke again. He was back to doing magazine covers.”

But for others, the productivity of Denslow’s Bermuda period isn’t at all surprising. For artists, even those who find themselves suddenly financially well-off, the need to keep creating never stops.

“He didn’t skimp on the work. He kept at it,” Frith said. “And I know how obsessive artists can be. Always drawing, catalogs and (other) things. I have a feeling Denslow was the same.”

Tom Butterfield agreed. It would have been out of character for an artist like Denslow to just take the Oz money and slow down.

“Denslow in his day would have probably been one of the people at the top of his field,” Butterfield said.

“I also think that those who are in creative fields, really creative fields, stop creating when they die. I think in the case of Denslow, despite his wealth, he kept going and going and going.”

Whatever the artist’s motivations, the failure of his Bermuda kingdom was a personal tragedy and remains a source of mockery to his legacy.

“I think he probably left here a broken man,” Paul Doughty said. “And when you think about somebody who has this kind of imagination and who was so involved in happy-ever-after and fantasy, that he could set himself up to lose big.” To be so, “‘God I could build my castle, I’m king so-and-so the first’” and then crash.

And so the Bermuda fairy tale came to an end.

The Bermuda Chapter Closes

In no time at all, the money ran dry. The artist mortgaged Denslow’s Island to Tietjens twice, the second time in 1911 after moving to Buffalo where he had found work with the Niagara Lithograph Co.

He was never able to pay back the loan and lost the island. Creditors circled; Frances left him.

Denslow never returned to Bermuda. Just like that, the kingdom was gone.

“He was at the top of his career when he moved down there,” said Hearn in a telephone interview. “The Pearl and the Pumpkin was going to be a big musical comedy. He worked on the libretto, he worked the costumes and the sets. He was very much involved in it.

“It wasn’t as successful as it might have been. They were hoping for another Wizard of Oz. And it just wasn’t comparable to that. It was OK. It did OK.”

Other projects also fell through. Another possible show and an unsuccessful book. And most importantly, The Wizard of Oz musical was winding down its national tour. The money just wasn’t coming in anymore, Hearn said.

“It was really what made Baum a wealthy man and Denslow as well,” Hearn said. “Then it was over. It was over by about 1910. That was a real cash cow until then.”

So was it all just a folly? A story for Bermuda tour boats to mock as they glide past his turreted home a century later?

Was it fate or bad business decisions that did him in? Or was the Oz artist simply ahead of his time?

To find possible answers, it helps to travel back to the Yellow Brick Road.

If we walk far enough, says Dorothy, we shall sometime come to someplace.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz — 1900

L. Frank Baum knew he had something special on his hands

In a letter to his brother Harry in April 1900, Baum wrote: “Then there is the other book, the best thing I’ve ever written, they tell me, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz … Denslow has made profuse illustrations for it and it will glow with bright colors.”

Baum had fully expected his new book to establish his reputation as a children’s novelist, according to The Road to Wicked.

He was no more an ordinary spinner of dreams than Denslow was. Among his many jobs through the years (traveling salesman and poet, among them), he had most recently edited The Show Window — a journal for window shop designers, according to the book’s authors, three American professors.

Advice included, “How to create perfect backgrounds” and “How to build stands and fixtures.”

But to really sell people stuff — late Victorians were discovering — you also needed eye-popping, buy-me color.

By the 1890s, research suggested that adults had “a surprising love of contrasts of highly saturated colors,” something advertisers at the time jumped to exploit, according to Chromographia — American Literature and the Modernization of Color by Professor Nicholas Gaskill of the University of Oxford.

It was a trend Baum encouraged in his journal, “publishing essays on the psychological impact of color combinations,” Gaskill wrote in his 2018 book.

More practically, he recommended that shops use “bright and varied” colored cheesecloth as backdrop in window displays to set off the products for sale.

“Baum instructed his readers to use the laws of color to incite in viewers a tingle of sensory intimacy, a feeling a presentness that could be transferred to the commodities,” Gaskill wrote.

It’s something Denslow, an accomplished poster and newspaper illustrator, understood as well.

This time, of course, the commodity would be a clever farm girl and a magical voyage.

Denslow and Baum Unite

Both gentlemen were ready for this moment. They made the perfect team.

After they met at the Chicago Press Club, Baum and Denslow soon collaborated on a number of projects, including the successful Father Goose, His Book, a collections of nonsense poetry, in 1899.

What came next was a brand new kind of children’s fantasy, one with a voice — a “matter-of-factness” as Baum biographer Dennis Abrams described it — that made it “distinctly American.”

It had something else too: to make the tale zing and pop — just like those shop windows, just like those theater posters — it had had color.

Lots of it.

The two partners believed so completely in the necessity of knockout color to tell their story that they paid for 24 full-color plates to be included in the book out of their own pockets. This was on top of another 130 monochrome drawings in grey, blue, green, yellow, red, and brown.

The adventurers in the book travel through color-coded regions, starting with the drab gray of Kansas and featuring a sparkling green Emerald City. Advances in printing techniques made all of this color possible.

A glow of bright colors indeed.

And it was a huge success.

The New York Times praised the book’s “bright and joyous atmosphere,” claiming “it will indeed be strange if there be a normal child who will not enjoy the story.”

It will glow with Bright Colors

Baum and Denslow had collaborated with just this “normal child” in mind. Sure it was a fanciful story, but it was purposefully designed.

One leading art critic of the day singled out Denslow especially for his skill in engaging young children.

In a 1903 essay, cited in Chromographia, J.M. Bowles condemned the “old monstrosities of picture-books” that he felt were too sophisticated for young children. He used Kate Greenaway as one example as someone whose work, he believed, was too grown-up.

Art for children, Bowles said, needs to “be truly simple” to engage young minds that are still maturing. It also needs vivid and striking color to hold their attention.

Denslow, Bowles felt, understood this perfectly.

The artist’s style — bold color patches and strong lines, “abstract blocks of pure hue that float on his pages” — was something “totally new,” Bowles said, and it delighted children.

The critic said he had seen “a baby of twelve months beam with delight as some of these pages (in the artist’s books) were turned, and fairly jump at color deliberately placed by the crafty Mr. Denslow.”

Bowles called him an “impressionist for babies.”

In his book, Gaskill builds on Bowles’ observations made more than a century ago, examining how modern color transformed U.S. literature.

Oz “outshone” every children’s book in 1900 and “reviewers never failed to remark on the book’s ‘uncommon images’ and ‘wild riots’ of color.

“Indeed, the very story of Oz, starting with the initial shift from the drab to the spectacular, is in many ways about modern color and its ability to excite viewers to a state of rapt wonder,” Gaskill said.

One of the book’s wonders is “its thorough intermingling of Denslow’s drawings with the printed words of Baum’s tale,” according to the professor’s research.

“We tend to think of Oz’s signature color trick as belonging to the (1939) film,” he said. “But when MGM wowed moviegoers with the sudden switch from sepia-toned Kansas to Technicolor Oz, they were only repackaging the move that Baum and Denslow had made 39 years earlier.”

But it was just this team effort that Baum himself wasn’t keen on promoting, something that certainly damaged Denslow’s perceived Oz role.

Over the years, critics have failed to recognize this colorful collaboration of art and story “so important for Oz’s lasting importance, not the least because Baum himself tried to hide it,” Gaskill said.

Baum and Denslow broke up after bickering over who was most responsible for the book’s success. After that, “Baum’s resentment — teamed with the expense of reprinting the book in its original splendor — ensured that subsequent editions of Oz appeared with different illustrators or with no drawings whatsoever.”

Likewise, “the collaborative component” of text and color was lost, Gaskill said.

And with it, for many years at least, Denslow’s unique role in telling the story.

A Librarian takes aim at Denslow

But professional jealousy was only one factor influencing Denslow’s Bermuda-era, post-Oz career.

He was also done in by a highly influential New York City Public Library librarian and firecracker named Anne Carroll Moore.

Moore, who pretty much invented children’s libraries in the United States, saw things differently than Bowles and other critics of the day who praised Denslow’s illustrations in Oz and other children’s books. And her influence spread far and wide.

In a 2008 article for The New Yorker, staff writer and Harvard University professor Jill Lepore wrote, “In the first half of the twentieth century, no one wielded more power in the field of children’s literature than Moore” and “she never lacked for an option.”

And it was “her verdict, not any editor’s, not any bookseller’s, (that) sealed a book’s fate.”

In 1945, near the end of her career, Moore went after E.B. White’s Stuart Little, his first children’s book, according to Lepore’s article. Moore accused White of blurring reality and fantasy and threatened to keep the book out of libraries and schools across the country.

This unsuccessful last battle marked the end of her decades-long, iron-grip influence on children’s literature.

In 1900, Moore was just getting going. Quite possibly, Denslow was one of the first targets for her vitriol.

At the time, Moore was still at the Pratt Institute Free Library in Brooklyn, according to American Picturebooks from Noah’s Ark to The Beast Within by book editor Barbara Bader. She particularly disliked what she called the “poster craze.”

Such books as Denslow’s Mother Goose in 1901 and others of the “comic poster order,” Moore wrote, “should be banished from the sight of impressionable small children.”

She found anything outside the faithful representation of nature as “primitive” and “degenerate,” according to Bader’s 1976 study.

Take, for example, the toy books, which Denslow had written when first arriving in Bermuda. These books had been well-received and a financial success.

But as another prominent librarian claimed, echoing Moore, “they failed to preserve the traditions of perspective, color values, forms and proportions” (without which children would “gain false notions of things.”)

The Curtain Falls

Likewise, “librarians and educators scorned them,” Bader wrote.

None of these outside factors takes away from Denslow’s own role in his late career downfall. The ambitious path he took after the financial and critical success of Oz was of his own choosing.

Nothing symbolized his undoing more precisely than the loss of his highly-publicized Bermuda island.

Was the kingship destined to fail?

Denslow was worn out when he arrived in Bermuda in 1903. He had fought with Baum and seemed determined to cut his own path in children’s books.

Could he be difficult? Was he too demanding of Baum after Oz? Both men had ego to spare, for sure, but it was more of a two-sided break-up than many writers over the years have contended.

But temperament was only one factor in the difficulties Denslow faced late in his career.

It’s clear he never found a creative partner to match Baum, that much historians and critics agree. But librarians and schools also banned his books, signaling that his “poster style” was possibly ahead of its time. And Baum himself tried to muddy his contribution to the success of Oz, his crowning achievement.

Could it have been that — before the Bermuda kingship, before The Pearl and the Pumpkin, before the dancing lilies — destiny was already brewing for Bermuda not to work?

Even when he lost his Bermuda castle and returned to the States — when his wife, the big contracts and the associated glory — were gone, Denslow never stopped drawing. When he died of pneumonia in 1915, at age 59, he had just landed a career-lifting job to draw a Life magazine cover titled, How Perfectly Absurd!

The island kingdom may have slipped from his fingers, but like so many artists who came and went, the artist left behind a legacy in Bermuda.

His white towered house — where he gazed across the harbor and imagined a childhood adventure to rival Oz — still overlooks The Great Sound today.

And those lilies he brought to life are still there. The shore-to-shore fields of the early 20th century are gone, but every spring lilies still appear in Bermuda — in pretty bunches on tables and small home gardens, in roadside crevices and drugstore pots — wild and cultivated both.

“Lily White my heart is yearning, Lily White to you I’m turning,” sang Canadian soprano Ida Hawley in 1905, as Pearl waits longingly for her Joe to appear. It was possibly the best thing going for that tepid “extravaganza” that long ago summer:

A lily field is the prettiest of the appeals in The Pearl and the Pumpkin … We see at first an expanse of lilies, cultured as they are in Bermuda for the Easter market in America. The light changes slowly, from dawn to sunrise. A girl comes into the field to pluck an armful of the flowers. She sings and dances while doing it. Then the front rows of the lilies pull themselves up from the ground, and are girls, white and dainty as the posies, with fleet feet in place of roots, agile limbs for stalks and smiling faces for the flowers.

The Salt Lake Herald — August 27, 1905

The song is but a “trifle,” but the Bermuda-inspired scene — created by Denslow — was “so surpassingly beautiful” that audiences loved it, one reviewer wrote.

And Pearl and Joe — in true fairy tale fashion — lived happily ever after as the curtain falls on the South Shore of Bermuda under the moonlight at midnight.

Bermuda may be that “fleck of sand” in the Atlantic where so many artists have found solace or something else, as Tom Butterfield of the Masterworks Museum of Bermuda Art said. Denslow found something there too. Perhaps not peace, or a happily-ever-after, but some inspiration.

Maybe even a good time.

As he proclaimed to the world so long ago:

“If you go to the Court of King Denslow, he will lay aside his sceptre — and his brushes — and make you know that he is glad to see you.”